The Art of Empathy

Recognition is Humanity's Primary Pursuit

The "still-face experiment" is a psychological experiment in which a caregiver (usually a mother) and her infant engage in normal face-to-face interactions, such as smiling, talking, and making eye contact. Then, the caregiver suddenly changes her behavior, maintaining a still, expressionless face (the "still-face"), and stops responding to the infant's actions. This change typically leads to noticeable stress responses in the infant, such as anxiety, agitation, or crying. After a period, when the caregiver resumes normal interaction, the infant usually gradually returns to the behavior exhibited at the beginning of the experiment.

Infants who are long neglected by their caregivers may develop a crisis of existence, which can cause lasting emotional and psychological harm.

Cold Family Relationships Build Emotional Walls

The quality of relationships determines the quality of life, and childhood relationships can have a lasting impact on one's quality of life.

Children coping with a harsh upbringing may unconsciously develop these four defense mechanisms:

- Avoidance: This is a defense mechanism born out of fear. Individuals choose to minimize emotions and relationships due to the harm caused by emotional and interpersonal connections. Such individuals feel most comfortable in superficial exchanges, tend to over-rationalize life, escape into work, strive for self-sufficiency, and pretend they have no needs. They often lack close relationships in childhood and hold low expectations for future interpersonal connections. These individuals may constantly be on the move, unwilling to settle down or be tied down; sometimes they may be overly proactive to avoid showing vulnerability; they manage to make themselves the strong ones others depend on but never seek help from others.

- Deprivation: Some children grow up around self-centered adults whose needs are ignored. Such children naturally learn the lesson that "my needs will not be met," which can easily transform into "I do not deserve to have." Those troubled by a deprivation model may feel worthless even after achieving remarkable success. They often carry the belief that there is some defect deep within them that, if known by others, would cause them to be abandoned. When treated poorly, they tend to blame themselves.

- Overreactivity: Children who grow up in dangerous environments often have an overactive threat detection system deep within their nervous systems. Such individuals interpret ambiguous situations as threats and perceive neutral faces as angry ones. They are trapped in an overactive mental theater, feeling that the world is full of danger. They overreact to situations without understanding why they do so.

- Passive Aggression: Passive aggression is an indirect expression of anger. It is a way for someone who fears conflict and struggles to handle negative emotions to avoid direct communication. Such individuals may grow up in a family where anger is frightening, emotions are unresolved, or love is conditional, learning that direct communication leads to withdrawal of love. Thus, passive aggression becomes a form of emotional manipulation, a subtle power game to extract guilt and love. For example, a husband with passive-aggressive tendencies might encourage his wife to go out with friends for the weekend, seeing himself as a selfless martyr, but becomes angry with her days before the outing and throughout the weekend. He will use various withdrawal and self-pitying behaviors to make her feel like a selfish person while portraying himself as the innocent victim.

The Dual Nature of Defense Mechanisms

These defense mechanisms do not always have negative impacts; they can be a form of overcompensation that leads individuals to extremes, and those who go to extremes may find it easier to achieve worldly success—many successful politicians, for instance, learn from childhood that life is a battle against injustice. Darkness gives them status, power, self-esteem, and resilience.

However, these benefits do not mask the problems caused by these defense mechanisms:

- Irrational hostility. They may believe that "all criticism and opponents are not only wrong but also evil."

- Individuals can be ensnared by their mechanisms. They may find themselves unable to control irrational actions.

- Old mechanisms become outdated. Old habits cannot adapt to the new era (conceptual blindness), such as fighting a modern war with the mindset of cold weapon warfare from World War I, leading to heavy casualties.

Repairing Issues? Communication is More Effective than Introspection

For various reasons, trying to repair the defense mechanisms stemming from a dark childhood through self-reflection often yields poor results. Communication with an external perspective is a more effective choice.

This is where empathy shines. Empathy is crucial at every stage of "knowing a person," and it is especially necessary when accompanying someone through trauma.

Empathy Sounds Easy but is Hard to Practice

If empathy is merely "I feel for you," it indeed sounds easy. However, empathy is a combination of a series of social and emotional skills. Some people are naturally good at these skills, but everyone can improve through practice.

Empathy involves at least three related skills:

- Mirroring

- Mentalizing

- Caring

Mirroring Emotions

People experience emotions in every moment of wakefulness through interactions with the external world. These emotions can be pronounced or subtle. The generation of emotions begins with sensations from every part of the body, transmitted through nerves to the brain, where they are monitored and recognized.

Historically, emotions were once considered a bad thing. For thousands of years, philosophers believed that reason was separate from emotion—reason was the cold, prudent driver, while emotion was the uncontrollable wild horse. This understanding is flawed.

In reality, emotions carry information. When not out of control, emotions are flexible mental abilities that help you navigate life. Emotions assign value to things: they tell you what you want and what you do not want. You pursue out of love and distance yourself out of disdain. Emotions help you adapt to different situations: when you find yourself in a threatening situation, you feel anxious, prompting you to quickly seek danger. Emotions also inform you whether you are moving toward your goals or away from them.

Thus, to understand a person, we should not only understand what they are thinking but also how they feel. These feelings are reflected in the other person's face, eyes, demeanor, and other parts of their body.

Masters of emotional mirroring can quickly experience the emotions of the person in front of them and can rapidly reproduce those emotions in their own bodies. Those skilled in emotional mirroring respond to smiles with smiles, yawns with yawns, and frowns with frowns. They unconsciously adjust their breathing patterns, heart rates, speaking speeds, postures, gestures, and even vocabulary levels to align with the other person. They do this because a good way to understand what another person feels in their body is to experience that emotion in your own body to some extent. Those who have received Botox injections and cannot frown may find it more difficult to perceive others' concerns because they cannot physically reproduce that emotion.

Masters of emotional mirroring have higher emotional granularity, allowing them to finely distinguish different emotional states and experience the world more precisely. They can accurately classify similar emotions: for example, anger, frustration, stress, anxiety, worry, and agitation.

Masters of emotional mirroring build a broad emotional vocabulary through reading literature, listening to music, and reflecting on relationships, enabling them to draw upon it skillfully in life, much like a painter having a wider palette of colors.

Mentalizing Emotions

Most primates can more or less mirror each other's emotions, but only humans can explain why the other person is experiencing their current emotions. This is also known as "projective empathy." When we connect our own memories with another person's current situation, we see more than just "this woman is crying"; we see "a woman who has suffered professional setbacks and public humiliation."

More advanced mentalizing helps us recognize the complexity of emotional states—people can experience multiple emotions simultaneously, and this complexity allows us to detach from empathy and make judgments.

Caring for Emotions

Many con artists are skilled at interpreting people's emotions, but we wouldn't say they are empathetic because they do not genuinely care for others. A child might see you crying and hand you a Band-Aid, but they cannot mentalize that you are crying because you had a tough day, nor can they know what you truly need at that moment.

Effective caring involves stepping outside of one's own experience and realizing that what you need in the same situation may be completely different from what I need. This is challenging; the world is full of "good people," but there are far fewer "effectively kind people." For instance, while some may need alcohol to cope with anxiety, others may need a hug.

Using the skill of caring for emotions, when you receive a gift from someone, write a thank-you note that focuses not on how you will use the gift but on the giver's intentions—what drove you to think this gift was suitable for me, and what you were thinking.

Similarly, cancer patients prefer "those who hug you, praise you, but do not make you feel like you are attending a funeral. Those who give you gifts unrelated to cancer. Those who just want to make you happy, rather than trying to fix you, reminding you that this is just another beautiful day with many interesting things to do."

Levels of Empathy

People with low empathy may think:

- I find it difficult to know what to do in social situations.

- If I am late to meet a friend, it usually does not bother me too much.

- People often tell me that I overdo it when I am making a point in discussions.

People with high empathy may think:

- Even if it does not involve me, interpersonal conflict is a physical pain for me.

- I often unconsciously mimic the gestures, accents, and body language of others.

- When I make a social mistake, I feel extremely uncomfortable.

In any field, truly creative thinking is simply this: a naturally exceptionally sensitive human being. For them, a touch is a blow, a sound is noise, a misfortune is a tragedy, a hint of joy is ecstasy, a friend is a lover, a lover is a god, and failure is death. Add to this fragile being a strong necessity for creation, constantly creating, creating, creating... Due to some strange, unknown inner urgency, they only truly live when they create.

-- Pearl S. Buck

High empathy sounds exhausting, but isn't it also moving? :)

How to Train Yourself to Increase Empathy?

-

Contact Theory: Organize a group of people to do things together to build bonds and promote mutual understanding. A community is a group of people with shared projects.

-

Observation and Performance: When people closely observe those around them, they become more empathetic. Actors are particularly good at observing and mimicking people; if you want your child to be more empathetic, encourage them to take drama classes at school.

-

Literature: Plot-driven books like thrillers and detective stories are less effective; what works are complex, character-driven novels like "Beloved" or "Macbeth."

-

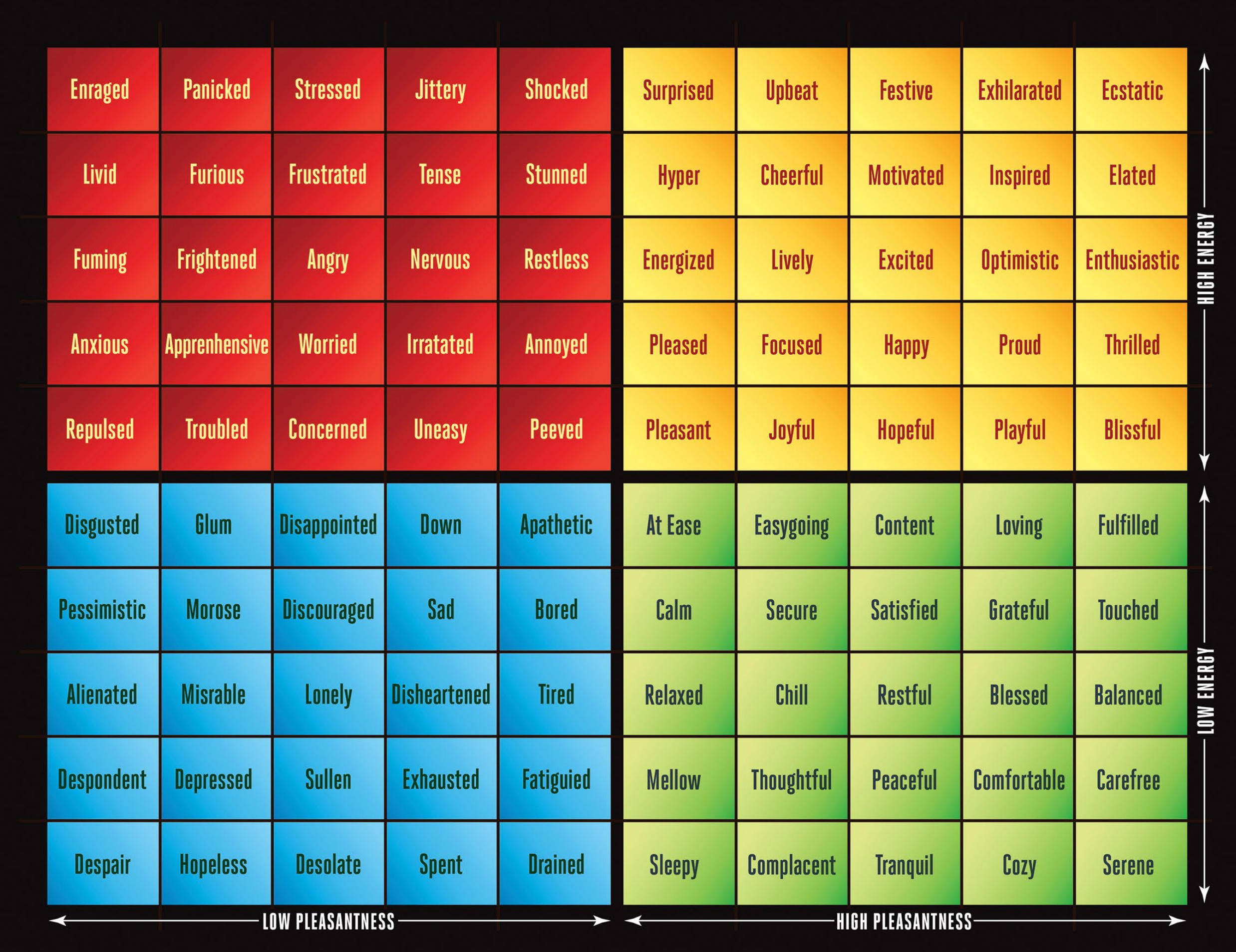

Discovering and Labeling Emotions: Occasionally pause to use Marc Brackett's mood map and the RULER (Recognize, Understand, Label, Express, and Regulate their emotions) method to identify, understand, label, express, and regulate emotions. Teams led by emotionally intelligent bosses report feeling inspired 75% of the time, while teams with lower emotional intelligence report only 25%.

-

Experiencing Suffering. Many truly empathetic people have experienced suffering but have not been crushed by it; they do not develop excessive defense mechanisms but instead expose their vulnerabilities to life and speak openly like heroes.

Conclusion

In summary, emotions are embodied, and empathy is not an intellectual activity but training your body to respond in an open and interactive way. The "rational brain" cannot persuade the "emotional body" to escape its own reality; thus, the body must personally experience different realities. Those with empathy can provide this physical presence.

Perception influences emotion, and emotion also affects perception. For example, when feeling afraid, our ears focus on high and low frequencies—the frequencies of screams or roars—rather than the medium frequencies of normal human speech. Anxiety narrows our attention and reduces our peripheral vision; happiness expands our peripheral vision.

Those who feel safe due to the reliability and empathy of others see the world as a broader, more open, and happier place.

And suffering is the badge of honor for practitioners of empathy. Playwright Thornton Wilder once described such a person's remarkable presence in the world: "Without your wounds, where would your power be? It is your regrets that make your low voice tremble into people's hearts. Even angels cannot persuade those suffering and clumsy children on earth, but those crushed by the wheels of life can. Only wounded soldiers can serve love."