Regulatory Storm: Dilemma and Opportunities in the Crypto Industry

Author: Phoenix Capital Management

Translator: BlockEden.xyz Team and Payton Chat

📌 A deep dive into the regulatory disputes and legal issues the crypto industry faces in the past, now, and predictably in the future.

TL;DR

- In the Ripple case, a partial victory was achieved in the programmatic sales, avoiding being recognized as securities sales. We have carefully analyzed the court's ruling logic and believe that there may be quite obvious errors in fact recognition, which has a high possibility of being overturned later.

- We've examined the historical origins and basic connotations of securities law, and believe that tokens narrated as "the project team is doing their job" are close to the securities law definition. Thus, a reasonably high proportion of tokens may be recognized as securities in the future. However, the current SEC's regulatory demands further exceed the reasonable scope of securities law.

- Staking/yield farming is more likely to be considered securities than token sales.

- Compared to the regulation of CeFi, the regulation of DeFi is at an earlier stage. In addition to securities law, more uncontroversial regulatory issues like KYC/AML are yet to be resolved.

- Even if a large number of altcoins are identified as securities, it would not signify the end of the industry. High market cap tokens are fully capable of seeking compliance in the form of securities; lower market cap tokens may exist in non-compliant markets for a long time but can still indirectly gain liquidity from compliant markets. As long as there is a clear regulatory framework, regardless of its nature, the industry can find new paths and models for long-term development.

Table of Contents

- Long-Awaited (Temporary) Victory - An Interpretation of the Ripple Case

- Howey Test, Orange Groves, and Cryptocurrency

- Why Securities Law Exists

- Project team is doing their job = Securities?

- Recap of SEC vs Ripple Labs

- A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security

- Looking forward - Where are the risks and opportunities?

- Securities law is not the only concern

- What if crypto loses? - Securities law won't kill altcoins

- Peace is More Important Than Victory

Long-Awaited (Temporary) Victory - An Interpretation of the Ripple Case

On July 13, 2023, Ripple Labs received a partial favorable ruling from the New York District Court, causing a significant surge in the crypto market. In addition to XRP itself, a series of tokens previously identified as securities by the SEC also experienced a substantial increase.

As we will discuss later, we are still far from the era when the crypto industry truly embraces clear regulation. However, without a doubt, this partial victory of Ripple Labs remains one of the most important events in the crypto industry in 2023.

Below are some of the major disputes between U.S. regulators and the crypto industry before the SEC vs. Ripple Labs case.

| Case | Date Settled | How it's Settled |

|---|---|---|

| SEC vs Block.one (EOS) | 2019/09 | Block.one Settles with SEC, Pays $24mn Fine |

| SEC vs Telegram | 2020/06 | Court Rules Telegram's Actions as Selling Unregistered Securities, Telegram Returns 18.5mn Fine |

| CFTC vs BitMEX | 2021/08 | Court Determines BitMEX Engaged in Illegal Derivative Trading (specific projects are too numerous to elaborate), BitMEX Pays $100mn Fine and Ceases Illegal Activities |

| SEC vs BlockFi | 2022/02 | BlockFi Settles with SEC, Seeks Business Compliance, and Pays $100mn Fine |

| SEC vs Nexo | 2023/01 | Nexo Settles with SEC, Shuts Down Lending Business, and Pays $45mn Fine |

| SEC vs Kraken | 2023/02 | Kraken Settles with SEC, Shuts Down Staking Business, and Pays $30mn Fine |

| CFTC vs Ooki DAO | 2023/06 | Court Determines Ooki DAO as an Illegal Futures Trading Platform, Orders to Shut Down All Business, and Pays a $644k Fine |

It's not hard to see that nearly all the major disputes so far have ended in failure or compromise by crypto companies.

We still want to say, this represents the first meaningful victory for the crypto industry in its battles against U.S. regulators, even if it is only a partial victory.

There have been many detailed interpretations of the court's judgment, so we won't elaborate here. Those who are interested can read the long Twitter thread by Justin Slaughter, Paradigm Policy Director:

Ok, having gone through the Ripple decision, here’s my takeaway:

Big loss for the SEC’s approach to crypto via focusing solely on enforcement, and this measurably increases the odds of crypto legislation passing this year.

Thread https://t.co/c4wOVPORVb

— Justin Slaughter (@JBSDC)

July 13, 2023

You can also read the original text of the court's ruling in your leisure time:

Plaintiff vs. Ripple Labs, Inc.

Before further interpreting this ruling, let's briefly introduce the core standard for the definition of securities in the U.S. legal system that you often hear about, the Howey Test.

Howey Test, Orange Groves, and Cryptocurrency

To understand the disputes surrounding all cryptocurrency regulations today, we must go back to sunny Florida in 1946, to the cornerstone case for today's securities law judgment, SEC vs. Howey.

(The following story outline was mainly written with the help of GPT-4)

📌 After World War II, in 1946, the company W.J. Howey owned a fertile orange grove in picturesque Florida.

To raise more investment, the Howey company launched an innovative plan that allowed investors to purchase land in the orange grove and lease it to the Howey company for management, from which investors could earn a portion of the profits. In that era, this proposition was undoubtedly very attractive to investors. After all, owning your own land was such a tempting thing.

However, the SEC did not agree. The SEC believed that the plan offered by Howey Company was essentially a security, but Howey Company had not registered with the SEC, which clearly violated the Securities Act of 1933. Therefore, the SEC decided to sue the Howey Company.

This lawsuit eventually ended up in the Supreme Court. In 1946, the Supreme Court made a historic judgment in the lawsuit of SEC vs. Howey. The court supported the SEC's stance, ruling that Howey Company's investment plan met the definition of securities, and therefore needed to be registered with the SEC.

The U.S. Supreme Court's judgment on Howey Company's investment plan was based on the four basic elements of the so-called "Howey Test". These four elements are: investment of money, expectation of profits, common enterprise, and the profits come from the efforts of the promoter or a third party. Howey Company's investment plan met these four elements, so the Supreme Court determined it was a security.

First, investors invested money to purchase land in the orange grove, which met the first element of the "Howey Test"—investment of money.

Secondly, the purpose of investors buying land and leasing it to the Howey Company was obviously to expect profits, which met the second element of the "Howey Test"—expectation of profits.

Third, the relationship between investors and the Howey Company constituted a common enterprise. Investors invested, and the Howey Company operated the orange grove, both working towards earning profits. This met the third element of the "Howey Test"—common enterprise.

Lastly, the profits in this investment plan mainly came from the efforts of the Howey Company. Investors only needed to invest money and could reap the benefits, which met the fourth element of the "Howey Test"—the profits come from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.

Therefore, according to these four elements, the Supreme Court judged that Howey Company's investment plan constituted a security and needed to be registered with the SEC.

This judgment had profound implications and formed the widely cited "Howey Test", defining the four basic elements of so-called "investment contracts": investment of money, expectation of profits, common enterprise, and profits come from the efforts of the promoter or a third party. These four elements are still used by the SEC to determine whether a financial product constitutes a security.

For purposes of the Securities Act, an investment contract (undefined by the Act) means a contract, transaction, or scheme whereby a person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party, it being immaterial whether the shares in the enterprise are evidenced by formal certificates or by nominal interests in the physical assets employed in the enterprise.

The above is an accurate interpretation of securities from the 1946 Supreme Court opinion, which can be broken down into the following commonly used criteria:

- An investment of money

- in a common enterprise

- to expect profits

- solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party

The charm of law is truly remarkable. It often employs abstract yet straightforward principles to guide the ever-changing specificities in real-life scenarios, no matter it is a citrus grove or cryptocurrency.

Why Securities Law Exists

In fact, how securities are defined is not important. Labeling something as a security or not doesn't make any substantive difference. The key is to understand what legal responsibilities stem from the economic nature of securities, in other words, why something possessing the four attributes of the Howey Test needs a separate legal framework for supervision.

The Securities Act of 1933, which predates the Howey Test by over a decade, explicitly answers the question of why securities laws are needed.

Often referred to as the "truth in securities" law, the Securities Act of 1933 has two basic objectives:

1) require that investors receive financial and other significant information concerning securities being offered for public sale; and

2) prohibit deceit, misrepresentations, and other fraud in the sale of securities.

"The fundamental starting point of securities law is simple - it's all about ensuring that investors have enough information about the securities they are investing in and are protected from deception. Conversely, the responsibilities imposed on the issuers of securities are straightforward, the essence of which is disclosure - they must provide complete, timely, and accurate disclosure of important information related to the securities.

The reason for such a goal of securities law is because securities, by their nature, rely on the efforts of third parties (active participants) for returns, which gives these third parties an asymmetric advantage over investors in terms of access to information and influence on securities prices. Therefore, there's a requirement for them to fulfill the duty of disclosure, to ensure that this asymmetry does not harm the investors.

There's no similar regulatory requirement in commodities markets because there are no such third parties, or in the crypto context, 'project teams'. Gold, oil, and sugar, for example, have no 'project teams'. The crypto market generally has a preference for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) over the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), but this is not due to personal preferences of the regulators that lead to differing attitudes towards crypto. The distinction between regulating commodities and regulating securities is based on the intrinsic differences between the two types of financial products. Because there are no 'project teams' with an asymmetric advantage, the regulatory framework for commodity law naturally tends to be more relaxed.

💡 The existence of a third party or 'Project Team' with an information and influence advantage is the fundamental reason for the existence of securities law; to curb the infringement of investors' interests by the third party/'Project Team' is the fundamental purpose of securities law; and requiring the 'Project Team' to provide complete, timely, accurate information disclosure is the main means of implementing securities law."

Project team is doing their job = Securities?

During my study of the history of U.S. securities law, a phrase often heard in the crypto industry led me to a simple and effective standard to determine whether a token is a security - that is, whether the investor cares whether the Project Team is active or not.

If the "the project team is doing their job" matters to investors, it implies that the return on this investment is influenced by the actions of the Project Team, which clearly meets the four criteria of the Howey Test. From this perspective, it's easy to understand why BTC is not a security, as there is no Project Team involved with BTC. The same applies to meme coins, they are merely digits in the ledger under the ERC-20 protocol, with no active Project Team behind them, and therefore are not securities.

If a Project Team is active and whether they perform well or poorly, or act at all, - whether it's in terms of technical upgrades, product iterations, marketing, ecosystem partnerships - has an impact on the token price, then the definition of a security is met. Given the existence of a Project Team, they possess information unknown to other investors and have greater influence on the token price, hence the need for regulatory oversight to ensure that they do not commit acts that harm the interests of investors. The logic of "the actions of the Project Team matter" → "the Project Team can reap the benefits"→ "the Project Team needs to be regulated by securities law" is a simple legal inference.

If you accept this logic, you can judge for yourself which tokens in the crypto space are reasonably classified as securities.

top search result of "项目方在做事" on Twitter

top search result of "项目方在做事" on Twitter

💡 In our view, if there is an expectation or concern among investors about the "the project team is doing their job," this token highly aligns with the definition of a security. From this perspective, it seems quite logical that a high proportion of tokens are classified as securities.

The current SEC wants more than just the basic regulations. As seen from Gary's public statements, he only recognizes that Bitcoin is not a security. For most other tokens, he firmly believes they should be classified as securities. The stance on a few tokens, like ETH, is relatively ambiguous. The CEO of Coinbase also recently mentioned in an interview that before the SEC sued Coinbase, it had demanded that Coinbase cease trading all tokens except for Bitcoin, a request that Coinbase refused.

We think it's unreasonable to classify pure meme coins without an operational project team or decentralized payment tokens as securities. The SEC's demands have exceeded the reasonable scope of securities laws, which has made it harder for the conflict between the industry and the SEC to be resolved simply.

You can read more on the topic in this article: SEC asked Coinbase to halt trading in everything except bitcoin, CEO says."

Recap of SEC vs Ripple Labs

- Let's briefly highlight a few key points:

- XRP itself is not a security, but we need to analyze the specific circumstances of XRP sales (such as the process, method, and channels of sale, etc.) to determine whether it constitutes a securities sale. We will elaborate on this point later: A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security.

- The court analyzed three forms of XRP sales separately: institutional sales, programmatic sales, and others. In the end, the first type, institutional sales, was considered as securities, while the other two were not.

- The reasons for judging institutional sales as securities sales are:

| Howey Test's Rules | Analysis |

|---|---|

| 1. An investment of money | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; institutional investors made payments to XRP, and Ripple Labs argued that not only is 'payment of money' required, but also 'an intent to invest'. This claim was rejected by the court. |

| 2. in a common enterprise | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; the funds invested by the investors were collectively received and managed by Ripple Labs, and what the investors received were the same fungible XRP tokens. |

| 3. to expect profits | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; 1) All the promotional materials from Ripple received by the investors clearly mention in various ways that the success of the Ripple protocol would drive up the price of XRP. 2) The existence of the lock-up clause directly proves that the investors' intent in purchasing XRP could only be investment and not consumption ('a rational economic actor would not agree to freeze millions of dollars'). |

| 4. solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; Ripple Labs explicitly linked the rise in XRP price to the technical advantages of Ripple Labs, the potential for widespread use of the product, the professional capabilities of the team, and successful market marketing in its promotions. |

-

The reasons for judging programmatic sales as not constituting securities sales are:

-

In this case, investors are not sure whether they are buying from Ripple Labs or other XRP sellers. Most XRP trading volume does not come from sales by Ripple Labs, so most XRP buyers have not directly invested their funds into Ripple Labs.

-

XRP buyers did not expect to profit from Ripple Labs' efforts, because:

-

Ripple Labs did not make any direct promises to these investors, and there is no evidence that Ripple Labs' promotional materials were widely disseminated among these investors.

-

These investors are less sophisticated, and it cannot be proven that they have a full understanding of the impact of Ripple Labs' actions on the price of XRP.

-

-

It's not hard to see that the court's judgement on programmatic sales is primarily based on the fourth item of the Howey Test, which is that these investors did not expect to profit from Ripple Labs' efforts.

-

The judgement of this district court does not have final binding force; it can almost be certain that the SEC will appeal. However, due to the lengthy legal process, it might take several months or even years before we see the results of a new appeal judgement. During this time, the judgement of this court will essentially form important guidance for the development of the industry.

Putting aside our position as cryptocurrency investors, and solely from the standpoint of legal logic, we believe that the court's logic in determining programmatic sales as not being securities is not very convincing.

📕 Here are two articles by seasoned legal professionals with similar opposing views. I recommend reading them if you have time, as our analysis also draws on some of their viewpoints.

First, we need to note the original text of the Howey Test: '...expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party...', which clearly points out that the source of profits can be the promoter or a third party, that is, it does not matter who the seller is. Or to say, it is not necessary for the source of the efforts to be the seller or promoter, as long as there is such a third party. Therefore, it does not matter who the investor buys from or whether the seller is the source of the returns. What matters is whether the investor realizes that the appreciation of the asset comes from the efforts of a third party. Therefore, the court's mention of blind buy/sell and the fact that buyers do not know whether they bought XRP from Ripple Labs or someone else is irrelevant to the Howey Test.

The real issue is whether investors in programmatic sales realize that the rise in the price of the XRP token they bought is related to the efforts of Ripple Labs. The court's main argument is that

- Ripple Labs has not directly promoted to retail, nor is there evidence that their materials (white papers, etc.) have been widely disseminated among retail,

- Retail does not have the cognitive abilities of institutional investors to recognize that the XRP token is related to the work Ripple Labs does in technology, product, and marketing.

First of all, this is a factual issue, not a logical one, which we can't demonstrate here. XRP is an old project, and we don't have a clear sense of what the retail investors were like at that time.

But from our limited experience, the vast majority of tokens with a project team are able to realize that the team's technical upgrades, early mainnet launch, better product, increase in TVL, ecosystem partnerships, KOL promotions, and other efforts have an impact on the price of the token they hold.

In the world of crypto, KOLs, Twitter, and Telegram groups large and small serve as the bridge between most project teams and users, the territory for outreach to retail investors. In projects big and small, we often hear discussions about how the 'community' is doing. Most project teams will have a token marketing/community team responsible for contacting exchanges around the world, hiring KOLs, and helping to disseminate project progress and important events.

💡We believe there is a bias in the court's fact-finding on programmatic sales in this ruling; we also agree with many legal professionals that there is a high likelihood that this part of the judgment will be overturned in the future.

(Just a week after writing this article, on the very day it was about to be published, we happened to see that the new judge in the SEC vs Terraform Labs case refused to adopt the judgment logic in the SEC vs Ripple Labs case - the logic being that no matter where the investor buys the token, it does not affect the investor's expectation that the efforts of the project team will influence the token's price.)

"Whatever expectation of profit they had could not, according to that court, be ascribed to defendants’ efforts," he wrote. "But Howey makes no such distinction between purchasers*. And it makes good sense that it did not. That a purchaser bought the coins directly from the defendants or, instead, in a secondary resale transaction* has no impact on whether a reasonable individual would objectively view the defendants’ actions and statements as evincing a promise of profits based on their efforts.**"

— Judge Rejects Ripple Ruling Precedent in Denying Terraform Labs' Motion to Dismiss SEC Lawsuit

☕️ By the way - Airdrops that don't require payment can also be considered securities sales.

This comes from an article by John Reed Stark. In the Internet bubble of the late 90s, several companies distributed free stocks to users via the internet. In subsequent legislation and trials, these actions were deemed securities sales. The reason is that although users did not pay money in exchange for these stocks, they gave up other values - including their personal information (required to fill in when registering for stocks) and increased attention for the companies distributing the stocks, which constituted a substantial exchange of value.

SEC Enforcement Director Richard H. Walker said at the time, "Free stock is really a misnomer in these cases. While cash did not change hands, the companies that issued the stock received valuable benefits*. Under these circumstances, the securities laws entitle investors to full and fair disclosure, which they did not receive in these cases.”*

A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security

Don’t be misled that Judge Torres ruled that sometimes XRP is a security and sometimes it isn’t. That’s exactly the opposite of what she ruled: XRP itself is NEVER a security. “ Page 15: "XRP, as a digital token, is not in and of itself a ‘contract, transaction[,] or scheme’…

— paulgrewal.eth (@iampaulgrewal)

July 14, 2023

As pointed out by Coinbase CLO Paul, this is the most important sentence in the entire judgement that people have not fully understood.

XRP, as a digital token, is not in and of itself a “contract, transaction[,] or scheme” that embodies the Howey requirements of an investment contract*. Rather, the Court examines the* totality of circumstances surrounding Defendants’ different transactions and schemes involving the sale and distribution of XRP.

Both of these judgments consistently express an important point of view:

A token is just a token - it's not like many people mistakenly believe that the court sometimes thinks XRP is a security and sometimes not - a token itself can never be a security.

What might constitute a security is the whole set of behaviors of selling and distributing tokens ('scheme'), there is no question of whether a token is a security or not, only whether a specific token sale behavior is a security or not. We can never come to the conclusion of whether it is a security or not just by analyzing a certain token, we must analyze the overall situation of this sales behavior ('entirety of …', 'totality of circumstances').

Both judges, whose opinions have significant conflicts, have insisted that it must be based on sales conditions rather than the attributes of the token itself to determine whether it is a security - this consistency also means that the possibility of this legal logic being adopted in the future is significantly higher than the judgment for programmatic sales, and we also believe that this judgment indeed has stronger logical reasonableness.

A token is just a token. A token is NEVER a security.

Digital tokens and stocks are fundamentally different. Stocks themselves are a contract signed by investors and companies. Their trading in the secondary market itself represents the trading and transfer of this contractual relationship. As the judge said in the Telegram case, digital tokens are nothing more than an 'alphanumeric cryptographic sequence', and they cannot possibly constitute a contract by themselves. They can only have the economic substance of a contract in specific sales situations.

If this legal point of view is accepted by all subsequent courts, then the future burden of proof on the SEC in the litigation process will be significantly increased. The SEC cannot obtain the regulatory power over all the issuance, trading, and other behaviors of a certain token by proving that it is a security. It needs to prove one by one that the overall situation of each token transaction constitutes a securities transaction.

The Court does not address whether secondary market sales of XRP constitute offers and sales of investment contracts because that question is not properly before the Court. Whether a secondary market sale constitutes an offer or sale of an investment contract would depend on the totality of circumstances and the economic reality of that specific contract, transaction, or scheme. See Marine Bank, 455 U.S. at 560 n.11; Telegram, 448 F. Supp. 3d at 379; see also ECF No. 105 at 34:14-16, LBRY, No. 21 Civ. 260 (D.N.H. Jan. 30, 2023)*

The Ripple case also explicitly pointed out that the court cannot determine whether the secondary sale of XRP constitutes a securities transaction. They need to assess the specific situation of each trading behavior to make a judgment. This greatly complicates the SEC's regulation of secondary transactions, and in some ways it may not be possible to complete; this essentially gives the green light to the secondary trading of tokens. Based on this, Coinbase and Binance.US quickly relisted XRP after the verdict was announced.

📕 There are some interesting discussions related to this in the Bankless podcast:

Bankless: How Ripple's Win Reshapes Crypto with Paul Grewal & Mike Selig

Again, it is still too early to consider this judgment as a definitive legal rule based solely on this case; but the legal logic of "A token is just a token" will indeed significantly increase the legal obstacles the SEC will face in regulating transactions of the secondary market in the future.

Looking forward - Where are the risks and opportunities?

The Sword of Damocles Over Staking

Sword of Damocles, 1812, Richard Westall

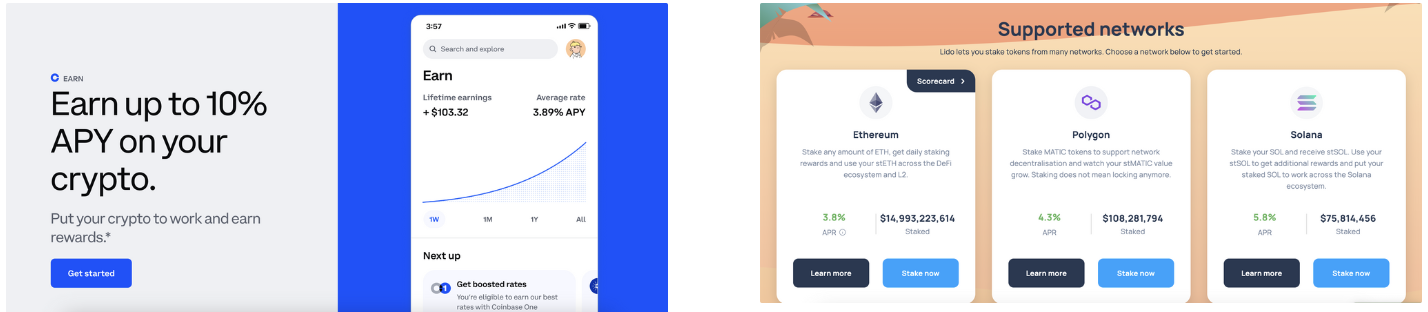

ETH staking has been one of the strongest tracks in the entire industry since 2023; however, the regulatory risks of staking services are still a Sword of Damocles over this super track.

In February 2023, Kraken agreed to a settlement with the SEC and shut down its staking service in the US. Coinbase, which was also sued for its staking service, chose to continue fighting.

Returning to the framework of the Howey Test, objectively speaking, there are indeed sufficient reasons for staking services to be considered securities.

| Howey Test's Rules | Analysis |

|---|---|

| 1. An investment of money | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; invest ETH |

| 2. in a common enterprise | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; invested ETHs are pooled together |

| 3. to expect profits | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; Investors expects staking yields |

| 4. solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party | ✅ It satisfies the criteria; staking yields come from the node operator's work and the node operator charges commission from the work. |

Kraken chose to settle. So, what are Coinbase's reasons for insisting that staking services are not securities?

Coinbase: Why we stand by staking:

At its most basic level, staking is the process by which users can contribute to the network by staking their token to secure the blockchain, facilitate the creation of blocks, and help process transactions. Users are not investing. Rather, users are compensated for fulfilling this important role through transaction fees and consensus rewards paid by the blockchain itself.

Coinbase makes an interesting statement, suggesting that "users who stake are not investing, but rather being compensated for the contribution they make to the blockchain network."

This statement is valid for individual stakers. However, as delegated stakers, they do not directly undertake the task of validating transactions or ensuring network security. Instead, they delegate their tokens to other node operators who use their tokens to complete these tasks. Stakers are not the direct laborers. In fact, they resemble the buyers of orange farm in the Howey case, owning land/capital (ETH), delegating others to cultivate (node operation), and obtaining returns.

Paying out capital is not labor, because the return from capital investment is a capital gain, not compensation.

Decentralized staking services are a bit more complex, and different types of decentralized staking might eventually receive different legal judgments.

The four criteria of the Howey Test are mostly similar in centralized staking and decentralized staking. The difference might lie in whether a common enterprise can exist. So, the staking model where all users' ETH is put into the same pool, even if it's decentralized, clearly also meets the four criteria of the Howey Test.

The argument in SEC vs Ripple Labs that allowed Ripple to win the Programatic Sales point (the buyer and seller don't know each other and there is no direct selling introduction), doesn't seem to protect staking services here neither.

Because apart from directly buying cbETH/stETH on the secondary market, in the case where stakers pledge their ETH to Coinbase/Lido and receive cbETH/stETH in return, it's clear that 1) the buyer knows who the issuer is, and the issuer also knows who the buyer is, and 2) the issuer clearly communicates to the buyer about the potential returns and explains the source of these returns.

Similarly, in addition to staking on PoS chains, many DeFi products that allow staking/locking tokens to earn yield are likely to meet the definition of securities. If it is somewhat challenging to establish a connection between the price of pure governance tokens and the efforts of the project team, the logic in the context of staking to earn yield is very straightforward and simple. Additionally, the reasoning in the Ripple case that made programmatic sales not considered securities also hardly stands here:

1) Users hand over tokens to staking contracts developed by the project team. The staking contract gives returns to users, and these returns are derived from the revenues generated by the project contracts that the project team opened.

2) During the interaction process between users and the staking contract, the contract also promotes and explains the returns to users, which makes it difficult to get away with the reasoning from XRP's programmatic sales.

💡 In summary, projects that offer staking services (in PoS chains, in DeFi projects) have a higher likelihood of being classified as securities due to

- clear profit distribution, and

- direct promotion and interaction with users.

This makes them more likely to be considered securities than projects that are generally "doing their job" by the project team.

Securities law is not the only concern

Securities law is the main focus of this article, but it's important to remind everyone that securities law is only a small part of the overall regulatory framework for crypto — of course, it's worth special attention because it is one of the stricter aspects. Whether a token is ultimately regarded as a security, commodity, or something else, some more fundamental legal responsibilities are common, and many regulatory agencies outside of the SEC and CFTC will get involved. The content involved here is worthy of another long article, we will just briefly give an example here for reference.

This is the responsibility related to Know Your Customer (KYC) centered on anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF). Any financial transaction must not be used for financial crimes such as money laundering and terrorist financing, and any financial institution has the responsibility to ensure that the financial services it provides will not be used for these financial crimes. To achieve this goal, all financial institutions must take a series of measures, including but not limited to KYC, transaction monitoring, reporting suspicious activities to regulators, maintaining accurate records of historical transactions, etc.

This is one of the most fundamental, undisputed basic laws in financial regulation, and it is a field jointly supervised by multiple law enforcement departments, including the Department of Justice, Treasury/OFAC, FBI, SEC, etc. Currently, all centralized crypto institutions are also complying with this law to perform necessary KYC on all customers.

The main potential risk in the future lies in DeFi, whether it is necessary and possible to make DeFi comply with similar regulations as CeFi, requiring KYC/AML/CTF; and whether this regulatory model might harm the foundation of blockchain value, permissionlessness.

From a basic principle point of view, financial transactions are generated in DeFi, so these financial transactions need to ensure that they are not used for money laundering and other financial crimes, so the necessity of regulatory law is undoubted.

The challenge mainly lies in the difficulty in defining the regulatory object, essentially these financial transactions are based on the services provided by a string of code on Ethereum, so is it the Ethereum nodes running this code, or the project parties/developers who wrote this string of code, who should be the regulatory object? (That's why there are controversial cases caused by the arrest of Tornado Cash developers.) In addition, the decentralization of nodes and the anonymization of developers make this oversight thinking even more difficult to implement — this is a problem that legislators and law enforcers must solve, it is questionable how they will solve these problems; but what is unquestionable is that no regulator will allow money laundering, arms trading and other activities on an anonymous blockchain, even if these transactions account for less than one ten-thousandth of the blockchain transactions.

Actually, just on the 19th of this month, four senators from the U.S. Senate (two Republicans and two Democrats, so it's a bipartisan bill) have proposed a legislation for DeFi, the Crypto-Asset National Security Enhancement and Enforcement (CANSEE) Act. The core is to require DeFi to comply with the same legal responsibilities as CeFi:

In an effort to prevent money laundering and stop crypto-facilitated crime and sanctions violations, a leading group of U.S. Senators is introducing new, bipartisan legislation requiring decentralized finance (DeFi) services to meet the same anti-money laundering (AML) and economic sanctions compliance obligations as other financial companies*, including centralized crypto trading platforms, casinos, and even pawn shops. The legislation also modernizes key Treasury Department anti-money laundering authorities, and sets new requirements to* ensure that “crypto kiosks” don’t become a vector for laundering the proceeds of illicit activities.

— Bipartisan U.S. Senators Unveil Crypto Anti-Money Laundering Bill to Stop Illicit Transfers

Ensuring Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorist Financing (CTF) in DeFi transactions is a key regulatory challenge beyond securities laws. Regardless of whether a token is classified as a security or commodity, there are strict rules against market manipulation. Resolving these issues in crypto is a future challenge for the industry.

Below are some typical forms of market manipulation. Anyone involved in crypto trading will likely recognize them.

Here are some common forms of market manipulation:

- Pump and Dump: This involves buying a security at a low price, artificially inflating its price through false and misleading positive statements, and then selling the security at the higher price. Once the manipulator sells their shares, the price typically falls, leaving other investors at a loss.

- Spoofing: This involves placing large buy or sell orders with no intention of executing them, to create a false appearance of market interest in a particular security or commodity. The orders are then canceled before execution.

- Wash Trading: This involves an investor simultaneously buying and selling the same financial instruments to create misleading, artificial activity in the marketplace.

- Churning: This occurs when a trader places both buy and sell orders at the same price. The orders are matched, leaving the impression of high trading volumes, but no net change in ownership.

- Cornering the Market: This involves acquiring enough of a particular asset to gain control and set the price on it.

- Front Running: This occurs when a broker or other entity enters into a trade because they have foreknowledge of a big non-publicized transaction that will influence the price of the asset, thereby benefiting from the price movement.

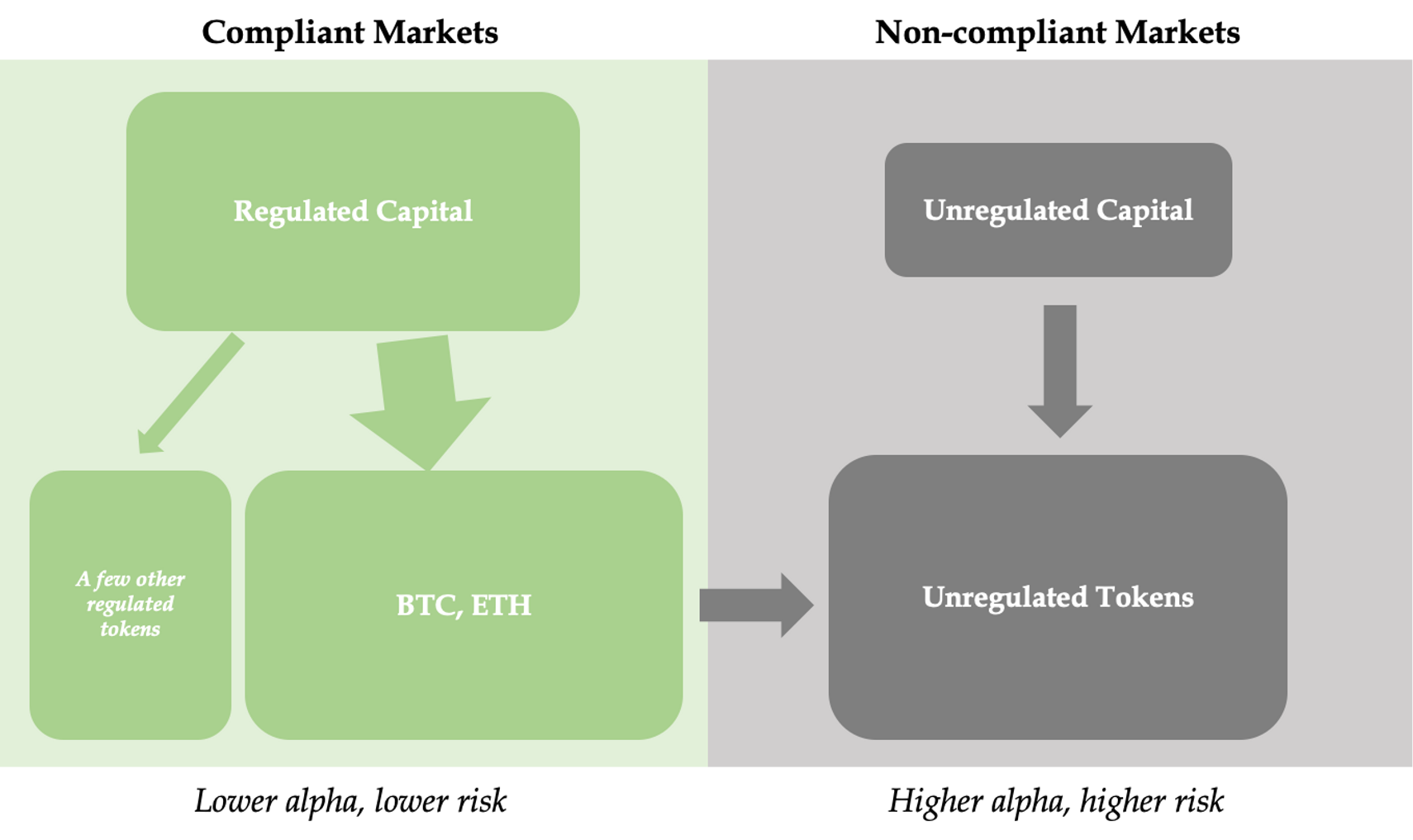

What if crypto loses? - Securities law won't kill altcoins

We lack sufficient legal and political knowledge to predict the outcomes of these legal disputes, but objective analysis leads us to acknowledge that the logic of U.S. securities law supports classifying most tokens as securities. So we must deduce or imagine what the crypto industry might look like if most tokens are considered securities.

Some tokens may choose to comply as securities

Firstly, purely from an economic perspective, the compliance cost of being publicly listed isn't as daunting as it might seem. For large-cap tokens with a FDV of over 1 billion, they are likely able to bear the cost.

A simple market value comparison reveals that many tokens have comparable market values to listed companies, especially those with a 1bn+ FDV. It's entirely reasonable to believe that they can handle the compliance costs of a listed company.

- The U.S. stock market has about 2000 companies with a market value of 100mn-1bn and about 1000 companies with a market value of 1bn-5bn.

- In the current bear market environment for altcoins, crypto has about 40-50 tokens with a FDV>1bn, and about 200 tokens with a FDV of 100mn-1bn. It's expected that more tokens will join the 100mn+/1bn+ value rank during a bull market.

We can also refer to some research on the compliance cost for listed companies. One relatively reliable source is the SEC's estimation of the listing compliance costs for small and medium-sized companies:

Their research shows that the average cost of achieving regulatory compliance to enter the marketplace as an IPO is about 1.5 million in ongoing compliance costs every year.

The conclusion is that there is a ~2.5mn listing cost, and a ~1.5mn ongoing annual cost. Considering inflation over the years, 3-4mn for an IPO and 2-3mn for annual recurring costs seem reasonable estimates. Additionally, these numbers positively correlate with the size of the company, and the costs for microcap companies worth hundreds of millions of dollars should be below these averages. Although it's not a small amount, for large project teams with hundreds of members, it's not an unacceptable cost."

"What's more uncertain is how to resolve these projects' historical compliance issues.

Listing a stock requires an audit of the company's financial history. Tokens, unlike equity, would need to disclose different content for listing, thus requiring a new regulatory framework for clear delineation. However, as long as there are clear rules, there are ways to adjust and deal with them. Companies with historical financial problems can also get the chance to go public by restating their historical statements.

While the cost of compliance is acceptable, it is also quite high; so, are project parties incentivized to do so? There's no simple answer to this question.

Firstly, compliance will indeed impose many burdens on many project parties and limit their operational flexibility. They cannot engage in "market value management," insider trading, false advertising, and coin selling announcements, etc. These restrictions affect the fundamentals of many business models.

However, for projects with particularly large market values, gaining greater market liquidity, accessing more deep-pocketed investors, and obtaining comprehensive regulatory approval are essential conditions for them to move to the next level, whether from the perspective of market value growth or project development.

"'Illegal harvesting' can be fierce, but the 'leek field' is small; 'legal harvesting' must be restrained, but the 'leek field' is large."

As the project scale increases, the balance between the potential benefits of non-compliance and the opportunities brought by the vast market and capital access post-compliance increasingly tips towards the latter. We believe that leading public chains/layer2s and blue-chip DeFis will take this step towards a completely compliant operational model.

Long-term coexistence and interdependence of compliant and non-compliant ecosystems

Of course, most project parties won't be able to embark on the road to securities compliance; the future crypto world will consist of both compliant and non-compliant parts, each with clear boundaries but also closely interconnected."

| compliant ecosystem | non-compliant ecosystem | |

|---|---|---|

| Capitals | Onshore institutional capital, low-risk-preference individuals | Offshore institutional capital, crypto-native, high-risk preference individuals |

| Underlying asset | BTC, ETH, a few compliant large-cap tokens | Most small and medium market cap tokens |

| Exchanges | Licensed onshore exchange, some regulated DEXs | Unlicensed offshore exchange, some unregulated DEXs |

| Features of the Market | Lower returns, lower volatility, safer and more transparent, more mature and stable | Higher returns, higher volatility, more opaque and risky, more innovation and opportunities |

| Complementarity | The price rise of mainstream coins and the asset appreciation will bring overflowing liquidity, which can still drive the price of small and medium-sized coins in the non-compliant ecosystem. | A more flexible and open environment nurtures new opportunities, and as small and medium-sized coins gradually grow, some will enter the compliant ecosystem. |

Such a coexistence pattern already exists today, but the influence of the compliant ecosystem in the crypto world is still relatively small. As the regulatory framework becomes clearer, the influence and importance of the compliant ecosystem will become increasingly significant. The development of the compliant ecosystem will not only significantly increase the total scale of the entire crypto industry, but also "transfuse" a large amount of liquidity to the non-compliant ecosystem through the rise in prices of mainstream assets and resulting liquidity overflow.

💡 Large projects will become compliant, while smaller projects can remain in the non-compliant market and still enjoy the overflow of liquidity from the compliant market. The two markets will complement each other ecologically, proving that securities laws will not be the end of crypto.

Peace is More Important Than Victory

On the judicial side, the SEC vs Ripple case has yet to be settled, and the SEC vs Coinbase/Binance cases have just begun - the settling of these cases could take several years.

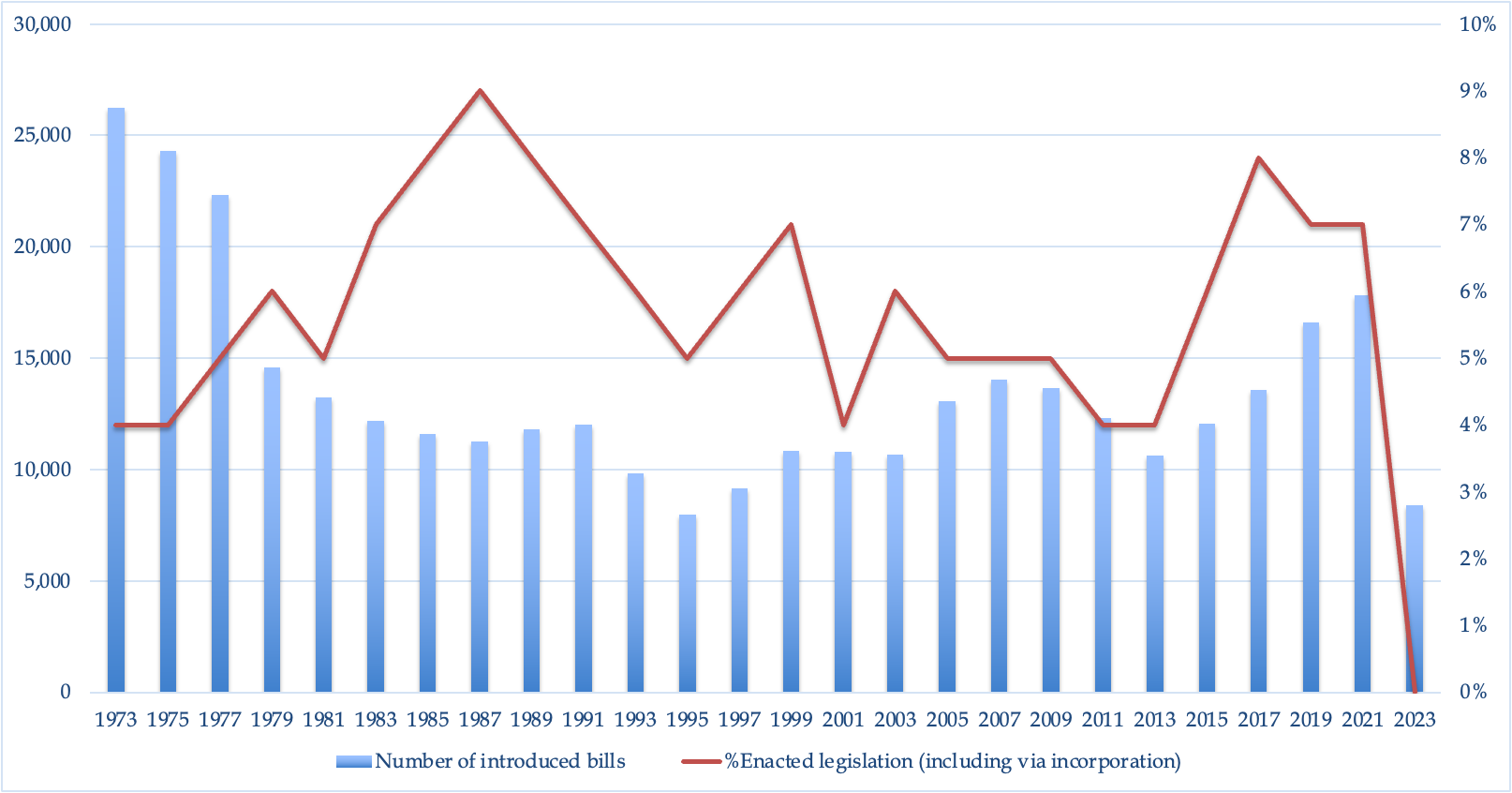

On the legislative side, since July, several crypto regulation bills have been submitted to both houses, including the Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act, Responsible Financial Innovation Act, Crypto-Asset National Security Enhancement and Enforcement —— Historically, more than 50 crypto-related regulatory bills have been submitted to both houses, but we are still far from a clear legal framework.

Statistics on the passing rate of bills in the US House of Representatives throughout history. On average, Congress receives about 7,000 bill submissions each year, with about 400 being enacted. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/statistics

The worst outcome for the crypto industry is not that most tokens will eventually be classified as securities, but the loss of time and space for the industry to grow, and the waste of resources and opportunities, due to the long-term lack of a clear regulatory framework.

The escalation and intensification of conflicts between regulators and the crypto industry is good news, as it means that resolution is nearing.

The verdict for Ripple Labs was announced on July 13, and the next day, July 14, is the anniversary of the French Revolution. This reminds me of the unrest in France after the revolution; but it was also during that chaotic time that the foundation of modern law - the French Civil Code - was born. I hope that we can see that, although the crypto industry is currently experiencing chaos and turmoil, it will eventually find its direction and way out, establishing a set of norms and codes that can coexist harmoniously with the outside world.

Code civil des Français

📎 Phoenix Capital Management is a fundamental-driven cryptocurrency hedge fund. The founding team has held key positions in several multi-billion dollar hedge funds. We strive to use a rigorous and scientific methodology, combining top-down macro research with bottom-up industry insights, to capture structural investment opportunities in the cryptocurrency industry and create long-term returns that transcend bull and bear cycles.

You can find all our writings here: Writings .

🤩 Hiring! We are actively searching for crypto researchers to join our team. If you are interested, please send your resume to [email protected]. Details can be found here.

Disclaimer:

This content is for informational use only and is not intended as financial or legal advice.

Any mistakes or delays in this information, and any resulting damages, are not the responsibility of the author. Please be aware that this information may be updated without notice.

This content does not promote or recommend the purchase or sale of any financial instruments or securities discussed.

The author may hold positions in the securities or tokens discussed in this content.