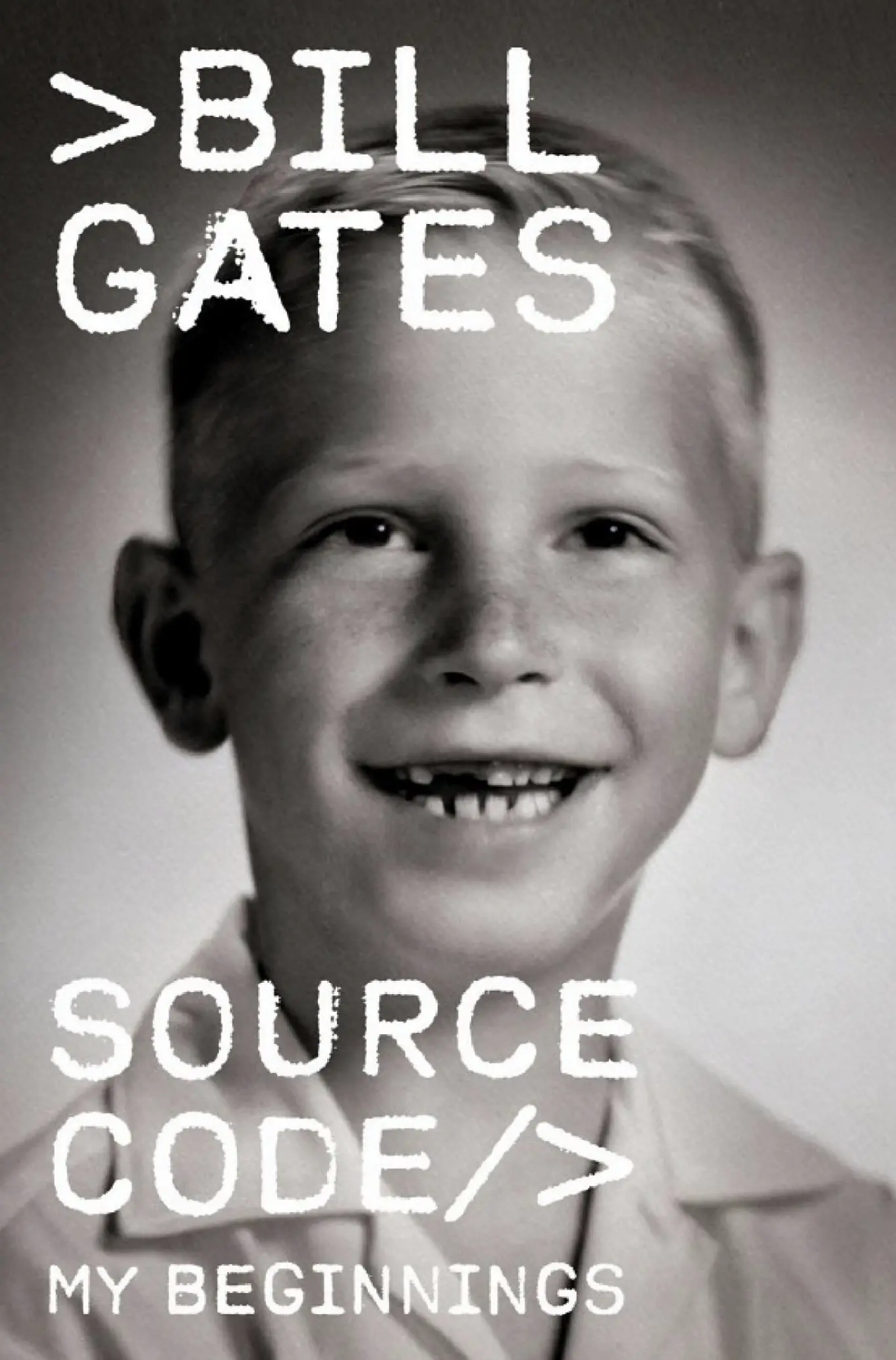

Source Code: My Beginnings by Bill Gates

Bill Gates’ Source Code: My Beginnings is the first volume of his memoirs, covering his life from childhood up to 1978 – the point where Microsoft, the company he co-founded, is poised to take off. Gates, known worldwide as a tech pioneer and philanthropist, uses this book to explore how his early experiences, family, friends, and passions formed the “source code” of who he is. The tone is candid and engaging, mixing personal anecdotes with reflections on the cultural and technological landscape of the 1950s–1970s. In clear and accessible language, Gates invites readers into his youth in Seattle, his formative adventures in computer programming, the triumphs and stumbles of adolescence, and the creation of Microsoft.

Prologue: The Hike that Sparked a Dream

The memoir opens with a vivid scene from Gates’ teenage years that encapsulates his dual love of exploration and technology. At age 13, Gates had joined a Boy Scouts group of older boys who undertook arduous week-long hikes in the Pacific Northwest wilderness. On these treks through the mountains, young Bill relished the freedom and challenge – navigating by map, carrying his gear, and bonding with fellow hikers around campfires. During one grueling hike in the Olympic Mountains, struggling through cold and snow, Gates found an unusual way to distract himself from discomfort: he started writing computer code in his head. He had recently heard about a new kind of personal computer and, without any machine in front of him, began mentally designing a new programming language for it as he trudged along. Focusing on the imaginary code helped him ignore the freezing wind and steep trail. In the end, the program he dreamed up couldn’t be tested at the time, but Gates notes that “the seeds of that coding language proved useful years later” when a suitable computer finally did come along. This prologue story highlights a central idea: even far from any computer, a young Bill Gates was already a programmer at heart, turning a tough wilderness experience into inspiration for a future software project. It sets the stage for the memoir by showing Gates as an intensely curious, driven teen, equally at home navigating physical and mental challenges. The freedom he felt in nature mirrored the freedom he found in coding – both arenas where a kid who didn’t always fit in socially could chart his own path.

Chapter 1: Trey

“Trey” was the childhood nickname of William Henry Gates III – “III” meaning the third, hence Trey. This chapter introduces Bill’s family background and early childhood, painting a picture of the environment that nurtured his young mind. Born on October 28, 1955 in Seattle, Bill grew up in an upper-middle-class family at a time when Seattle was coming into its own. His father, Bill Gates Sr., was a World War II veteran-turned-lawyer from humble origins, and his mother, Mary Maxwell Gates, was the daughter of a well-to-do Seattle family. Bill’s parents were a loving and dynamic duo – his dad an affable, principled attorney, and his mom a energetic community leader involved in charities and civic affairs. From the start, they instilled in “Trey” and his two sisters (Kristi and Libby) the importance of education and hard work.

One of the early influences on Bill’s thinking was his paternal grandmother, whom he called Gami. Gami was a strong-willed, sharp card player and a devotee of Christian Science. When Bill was a little boy, she taught him to play card games like Hearts and Bridge, which turned out to be more than just fun. Bill absorbed lessons in pattern recognition, strategy, and mental focus from those hours with his grandmother. Gami’s influence is something Gates later credits as an early training in logical thinking – a skill that would be invaluable once he met his first computer.

Seattle itself also played a role in young Bill’s imagination. In 1962, when Bill was 6 years old, the city hosted the Century 21 World’s Fair, a grand exposition celebrating science and the future. Bill’s parents took him to the fair, and even as a first-grader he was captivated by the exhibits of space-age technology. Decades later he recalls how “the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle was all about progress and innovation, and even at the age of six, I was fascinated by the possibilities of the future.”. Seeing things like space rockets, computers, and the iconic Space Needle sparked his sense of wonder. Gates describes this as an early “aha” moment when he realized technology could be world-changing – a seed planted in his young mind.

Overall, Chapter 1 (“Trey”) paints a portrait of Gates as a bright, curious child growing up in a nurturing environment. He was a bit different from other kids – extremely intense, highly intelligent, and sometimes prone to getting lost in thought. But he was also surrounded by people and experiences that fed his mind. By the end of the chapter, we see Bill as a grade-schooler who devours books, loves games of strategy, and is keenly aware of the exciting world of science and innovation around him. All the ingredients for a future inventor were present, even if no one yet knew how they’d mix.

Bill Gates (front, in white sweater) as a child in the 1960s, pictured with his mother Mary, father Bill Sr., and sisters Libby (infant) and Kristi. Gates’ family provided a supportive and stimulating environment for his curious mind.*

Chapter 2: View Ridge

As Bill entered elementary school, his intellectual appetite truly bloomed. Chapter 2, named after the View Ridge neighborhood of Seattle (where Bill’s school was located), recounts how young Gates became an insatiable reader and a precocious student. He loved nothing more than to bury his nose in a book – from science fiction novels to encyclopedias – and this constant reading dramatically expanded his knowledge and vocabulary at a very early age. Teachers noticed his advanced abilities; by second and third grade, Bill was reading far above grade level and charming adults with his knowledge on all sorts of topics.

His school recognized his talent and gave him special responsibilities. For example, Bill was allowed to help out in the school library, where he happily spent hours organizing shelves and recommending books to other kids. This not only fed his love of books but also gave him confidence. He began to see himself as someone who was really good at something (academics and intellectual pursuits), which in turn made him more assertive. Perhaps a little too assertive – young Bill developed a habit of questioning authority and challenging rules when they didn’t make sense to him. If a teacher said something Bill found illogical, he would blurt out a correction or argue his point. At home, if his parents set a rule he didn’t like, Bill would push back defiantly. He wasn’t trying to be bad; he genuinely believed he was right most of the time, and he loved to debate.

This chapter shows that alongside Bill’s brilliance came a streak of rebelliousness. By age 10 or 11, he had earned a reputation as a “smart aleck”, the kid who always had a comeback. He could be obstinately independent and even abrasive in how he spoke to adults. Family dinners in the Gates household grew tense as Bill sparred with his mother in particular. Mary Gates wanted her son to be polite, social, and well-rounded, but Bill was often dismissive of activities he considered a waste of time and would sass back with sarcasm. One of his favorite retorts (which he used often) was “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard!” – aimed at anything he disagreed with. This sharp tongue tried his parents’ patience greatly.

Trouble came to a head as Gates neared the end of elementary school (around age 11–12). In one oft-retold incident, during a particularly heated dinner-table argument, Bill shouted at his mother in frustration. Mary had been urging him to something mundane (perhaps clean his room or be on time), and Bill snapped back with a disrespectful comment. This was the final straw for his usually composed father. Bill Gates Sr., in a rare flash of temper, grabbed a glass of water and threw it in Bill’s face. The entire family was stunned – Bill himself certainly didn’t expect that reaction. Dripping wet, he replied with a trademark quip (“Thanks for the shower!”) but then fell silent. It was a turning point. “I had never seen my gentle father lose his temper,” he later reflected, and “to see how I had pushed my dad to that extreme was a shock.”. Bill realized his behavior at home had truly spiraled out of control.

After that episode, Bill’s parents took action to address his difficult behavior. They decided to enlist professional help: therapy for young Bill. At age 12, he began seeing a child psychologist – a highly unusual step in the late 1960s, but the Gates family was desperate for harmony. Thus ends Chapter 2 with the Gates family hopeful that some guidance might help their brilliant but headstrong boy.

Chapter 3: Rational

In Chapter 3, Bill’s memoir delves into his experiences in therapy and the changes it brought about – a phase that taught him to approach life more “rationally” (hence the chapter title). Starting therapy at 12 was not easy for Bill. In the first session, he recalls, his whole family attended – a clear sign that “everyone knew we were there because of me.” He felt embarrassed and resistant at first, but over about two and a half years of counseling, something shifted inside him.

Through conversations with the therapist, Bill slowly gained perspective on his relationship with his parents. He began to see that his mom and dad weren’t trying to control him for no reason – they genuinely loved him and wanted the best for him, even if he found their rules annoying. He also came to a sobering realization: he wouldn’t be a kid under their roof forever. This was a key insight. The therapist helped Bill understand that in just a few short years, he’d be off to college and on his own, and all the battles he was waging against his parents would become irrelevant. In Bill’s own words, he recognized that his parents “were actually my allies in terms of what really counted” and that “it was absurd to think that they had done anything wrong” by setting expectations for him. Essentially, he learned that his folks were on his side, not adversaries.

As he accepted this, Bill’s attitude began to mellow. He learned techniques to rein in his temper and communicate more respectfully. If something upset him, he tried to talk it out or channel his energy into a project, rather than immediately blurting out an insult. This was a very rational approach to dealing with emotions – analyzing the situation and deciding on a better response. The therapy also encouraged Bill’s parents to give him a bit more autonomy in exchange for him behaving more responsibly. Bill says this period taught him a lot about himself: he started to understand his own intensity, and how to harness it productively instead of letting it spark constant conflict.

By the end of Chapter 3, the Gates household was much calmer. Bill would always be a uniquely driven individual (that wouldn’t change), but now he had a clearer sense of boundaries and empathy. He could see the logic in working with his parents rather than against them. This newfound peace came just in time, because Bill was about to enter a dramatic new phase of his life – switching to a new school that would introduce him to computers and change his trajectory forever.

Chapter 4: Lucky Kid

With the family conflicts largely resolved, Chapter 4 reflects on how fortunate Bill was to have the support and opportunities he did. In fact, during therapy his counselor once remarked to him that he was a “lucky kid”, meaning that despite all the turmoil he generated, Bill had a lot going for him. In this chapter, Gates acknowledges the truth of that statement.

First and foremost, Bill came to appreciate his parents’ patience and wisdom. After the stormy pre-teen years, Mary and Bill Sr. remained steadfast in their love for him. They didn’t give up on their son; instead, they found a way to help him channel his gifts. In the memoir, Gates paints a warm portrait of his mom and dad as “wise, measured, caring, principled, and deeply community-oriented” people. He even jokes that they seem saintly for putting up with his earlier defiance. The “water-in-face” incident aside, the Gates really were exceptionally supportive parents.

Bill’s mother, Mary, comes through as a significant figure. She was determined to see Bill develop social skills and manners, not just intellect. By pushing him into activities outside his comfort zone (like volunteer work or attending varied events), she quietly shaped his ability to interact with others – something Bill later admits was invaluable. His father, meanwhile, encouraged Bill’s curiosity while teaching him about responsibility and humility.

The title “Lucky Kid” also applies to external circumstances. Bill realizes he was lucky to be born at the right place and right time. Seattle in the 1960s was an exciting environment for a budding geek. It was a city benefiting from big scientific and industrial enterprises (like Boeing and the University of Washington), yet small enough that a curious kid could access resources and mentors without too many barriers. And Bill’s family’s socio-economic status meant he went to excellent schools and never had to worry about basic needs – advantages not everyone has. Even the timing of the computer revolution was fortuitous: computers were just moving from exclusively military/industrial machines to things students and hobbyists might use, precisely when Bill was a teenager ready to dive in. He notes later that a lot of his success comes down to this historical luck.

At the end of Chapter 4, Bill is about to start 7th grade at the private Lakeside School. His parents, seeing his unbridled potential (and probably wanting a more challenging environment for him), decided to enroll him in this elite school. Lakeside had a reputation for rigorous academics – and, fatefully, it would soon have its own computer. As Bill transitions to this new school, he carries with him the lessons of the past few years. He’s calmer, more cooperative at home, and brimming with anticipation. In a closing reflection, Gates reiterates that being “different” might have made childhood hard at times, but it became his strength – and he was indeed lucky to have adults who understood and nurtured that difference. With a stable home and a bright educational path ahead, the “lucky kid” is poised to make the most of the opportunities coming his way.

Chapter 5: Lakeside

Chapter 5 dives into one of the most pivotal chapters of Bill Gates’ youth: his years at Lakeside School. Lakeside was a private, all-boys (at the time) prep school in Seattle, and Bill started there in 7th grade (around 1967). The chapter’s title is simply “Lakeside,” and it chronicles how this school became the breeding ground for Gates’ love of computers and his early partnerships.

Initially, the transition to Lakeside was not easy for Bill. Coming from public grade school, where he had often been the class clown and the resident genius, he thought he could continue his jokester persona. It didn’t work at Lakeside. The school was full of smart, confident boys, many from prominent families, and teachers who expected discipline. Bill’s antics earned him poor grades and some reprimands early on. He suddenly found that if he wanted to stand out, he couldn’t just coast on raw ability – he had to actually apply himself. This was a valuable lesson: effort and focus mattered.

Despite the rocky start, Lakeside offered something that lit Bill’s world on fire. In 1968, partway through Bill’s second year there, the school invested in a teleprinter terminal connected over phone lines to a General Electric time-sharing computer off-campus. This was an extraordinary thing in the 1960s – few high schools had any kind of computer access. Lakeside’s mothers’ club had actually raised funds for the terminal. The moment young Bill Gates laid eyes on that teletype machine, his life changed. He was instantly captivated. Here was a machine that would obey your instructions – but only if you told it exactly what to do in a language it understood.

Gates and a handful of other curious students crowded around the terminal after school, teaching themselves to program through trial and error. The first program Bill wrote on the Lakeside computer was a simple tic-tac-toe game, where you could play against the machine. Then he moved on to a more ambitious project – a simulation of the lunar lander (NASA’s moon landing was the talk of the time, and he created a game where you had to land a spacecraft by adjusting thrust). Writing these programs taught Bill a profound lesson: computers are completely literal. If your code had any mistake, the computer would not “figure out” what you meant – it would just fail. So Bill learned to concentrate deeply and be precise in his thinking, because a misplaced character could crash a program. This meshed well with his logical mind, and he thrilled in the challenge of debugging code to make it perfect.

During this period, two key friendships formed. Paul Allen, a quiet older student with a love for computers, noticed Bill’s enthusiasm. Paul was in 10th grade when Bill was in 8th, and he had more experience with the machine. Paul loved to poke fun at Bill, using a bit of reverse psychology – he’d say, “I bet you can’t solve this programming problem,” knowing full well that would spur Bill to prove him wrong. It worked: Bill would hunker down to tackle whatever challenge Paul threw at him. Before long the two became inseparable computing buddies, spending countless hours pushing the limits of what they could do with Lakeside’s limited computer access.

The other friend was Kent Evans. Kent was in Bill’s grade and, like Bill, something of an outsider at first. They bonded not over coding (Kent wasn’t a programmer) but over intellectual debates and shared ambition. Kent loved talking about big ideas – history, business, politics – and he encouraged Bill to think beyond just nerdy pursuits. They also both loved the outdoors; Kent, an Eagle Scout candidate, got Bill involved in some of the more adventurous school camping trips. Kent became Bill’s best friend (Gates describes him as “by far my closest friend” in those days), and their friendship balanced Bill’s life: with Paul he’d obsess over code, and with Kent he’d argue about world events or go climb a mountain.

By the end of Chapter 5, Bill Gates is around 13–14 years old and has truly found his passion. Lakeside School turned out to be the perfect incubator for his young talent. He has tasted both failure (bad grades for goofing off) and **success (writing programs that actually work)】 during these early high school years. Importantly, he’s met Paul Allen, who will play a huge role in his future, and Kent Evans, who has broadened his horizons. We see Bill transforming from a mischievous kid into a focused young technologist. The stage is set for him to push his abilities even further – and also for some dramatic twists that life had in store.

Chapter 6: Free Time

In Chapter 6, Gates recounts a dramatic twist in his Lakeside days – one that ironically gave him the “free time” to develop other aspects of his life. As Bill and his buddies got more and more into programming, they started to push boundaries. By 8th grade, Bill, Paul Allen, and a couple of other boys were spending virtually every spare minute punching programs into the school’s computer terminal. They even skipped classes or snuck out of home at night to get extra time with the machine (at one point, Bill was caught taking city buses solo to the University of Washington in the late hours to use their computers – that’s how hooked he was).

The computing time wasn’t free – Lakeside paid for hours on the GE time-share system – and the boys quickly used up the school’s budget. Desperate to keep coding, they got creative. Paul Allen, Bill Gates, and their friends found some glitches and loopholes to exploit extra computer time without paying. In one notorious caper, they discovered an administrative password that allowed unlimited access, and they joyfully rode that until they were caught. When the school (and the company providing the computer time) found out these 13-year-olds had basically been hacking the system, the boys were punished with a ban – they were barred from using the computer for the rest of the school year. For Bill, this was like having the candy jar put on the highest shelf: torture.

Suddenly, Bill had an unwanted abundance of free time. No more afternoons in the computer room; he had to find something else to do. Surprisingly, he didn’t simply mope (well, maybe a little at first). Instead, he threw himself into other pursuits. One was reading – even more than before – but another, very healthy outlet was outdoor adventure. Remember those scouting trips Kent Evans had involved him in? Bill stepped those up. He joined a Boy Scouts troop renowned for wilderness camping and spent that spring and summer going on extensive hikes and overnight treks. The same kid who could stay up all night debugging code now applied his energy to climbing hills with a pack on his back. And he loved it. Out in the forests and mountains, Bill found a different kind of challenge and freedom. There were no rules except survival and teamwork. He had to work with fellow scouts to ford rivers, cook over campfires, and navigate trails. These experiences built his confidence and endurance. His parents were actually pleased – their once obstinate son was now learning self-reliance and cooperation in the wild, of all places.

Yet, even on those long hiking expeditions, Bill’s mind never strayed far from computers. The chapter recounts the extraordinary anecdote (also mentioned in the Prologue) of how, on one especially brutal multi-day hike in the mountains, Bill’s mental refuge was to write code in his head. Night would fall, the temperature would drop, and while the other scouts shivered in their sleeping bags, Bill lay there pondering how to optimize a piece of software. It was during this “computerless” period that he conceived the idea for a new programming language suited for a small personal computer someone had described to him. He had no computer to test it on, but he scribbled notes when he could. It was like solving a giant puzzle entirely in the abstract – and he found it exhilarating. Though he couldn’t implement this idea at the time, a few years later, it would resurface when he encountered a real personal computer that needed a language (foreshadowing the Microsoft BASIC project).

By the time the ban on computer use was lifted, Bill had grown in multiple ways. He was more physically fit, more well-rounded, and probably more appreciative of having access to a computer when it was returned to him. Chapter 6 thus shows a Bill Gates who is becoming adaptable and resilient: when one passion was temporarily taken away, he developed himself in other areas. The title “Free Time” is a bit tongue-in-cheek – free time, to Bill, was just time he filled with other intense learning experiences. Little did he know that soon, he’d get more computer time than he ever dreamed of, under some very interesting circumstances.

Chapter 7: Just Kids?

Chapter 7 covers the period when Bill was about 15–16 years old (9th and 10th grades), and it’s a tale of teenagers doing adult-level things – hence the title “Just Kids?” with a question mark. The chapter narrates how Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Kent Evans turned their computing hobby into a paid enterprise, and how they dealt with responsibilities and tragedy along the way.

It all started when the group’s reputation for programming around Seattle began to spread. A local technology company called Computer Center Corporation (CCC) had taken note of these Lakeside whiz kids. Impressed by their skills (despite the fact they’d been banned for mischief), CCC made an offer: the boys could have unlimited computer time in exchange for helping find bugs in the company’s software. Bill and his friends jumped at the chance. This was like a dream – free access to a powerful PDP-10 computer. They spent countless hours at CCC, honing their programming by testing the system to its limits. It was an unstructured, hands-on education in coding that no formal class could have provided. Bill later would credit this period as absolutely formative – he was programming more than 20 or 30 hours a week, becoming fluent in multiple programming languages while still in 9th grade.

Buoyed by their success at CCC, Bill, Paul, and Kent formalized their partnership by creating the “Lakeside Programming Group.” Imagine three lanky teenagers forming what was essentially a software startup in 1970 – long before the word “startup” was common. Through a family connection, they landed a real contract with a company in Portland, Oregon called ISI (Information Sciences Inc.). ISI needed a payroll program written for a mid-size computer system, and they figured why not hire these prodigy kids who charge less than professional programmers. Bill and his friends were thrilled – and perhaps a bit intimidated – to have a paying client counting on them. They would take the bus from Seattle to Portland on weekends to work at ISI’s office (since they were obviously not old enough to drive). At first, some employees at ISI looked at them skeptically, as if to say “They’re just kids – can they really do this?” But Bill was determined to prove their worth. He and Paul shouldered most of the coding while Kent helped manage the project and communications.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. The stress of a real-world project caused friction within the trio. Kent, ever the ambitious planner, sometimes clashed with Bill over how to proceed; Paul’s and Bill’s coding sessions could stretch till dawn, which worried Kent about meeting deadlines. At one point, Kent even felt Bill wasn’t pulling his weight on documentation or that Bill was too headstrong in decisions. These were normal growing pains of a young team learning to work together (something Bill would face later at Microsoft too). In the end, however, they delivered the payroll system successfully. The client was satisfied, and the Lakeside Programming Group got paid – giving them both money (which probably went straight into buying more computer time or equipment) and a huge confidence boost. They weren’t just kids anymore; in this field, they could compete with adults.

Back at Lakeside, the school itself soon needed these students’ expertise. Lakeside was expanding and, for the first time, admitting girls, which doubled the student body. Suddenly, creating class schedules (who takes what class when) became a complex logistical puzzle. The administration asked Bill and Kent if they could write a program to automate the class scheduling for the school. They agreed – it was exactly the kind of challenge they loved. Paul Allen also assisted in this behind the scenes, though he had graduated by then. Bill and Kent spent months on this project, working closely with school staff to encode all the rules and preferences into the system.

Then, shockingly, tragedy struck in early 1972. Kent Evans died in a mountaineering accident during a climb with a church group in the Cascade Mountains. A misstep, a fall – and Bill’s best friend was gone at age 17. The news devastated Bill. Kent had been his daily companion, the one who could match Bill’s intellect and challenge him to be better. Gates recalls this as the first time he had to confront death and deep grief. It felt horribly unfair – “They seemed destined to work together as adults,” one account noted, and one can only imagine what “Bill and Kent as a founding duo” might have achieved if Kent had lived.

In the aftermath, Bill did the only thing he knew how: he threw himself even more into the work as a coping mechanism. He and Paul Allen, both mourning Kent, redirected their grief into finishing the Lakeside scheduling program with fervor. They locked themselves in the computer room for marathon sessions, determined to get it right as a tribute to their friend. In those intense weeks, Bill and Paul grew closer than ever – their partnership cemented by shared loss and a shared mission. They successfully completed the scheduling software, which worked and was implemented at Lakeside, saving the school administrators untold hours of manual scheduling.

Chapter 7 is thus filled with mixed emotions: the pride of youthful accomplishments and the pain of losing a friend. The title “Just Kids?” underscores a theme – these teenagers did things normally reserved for adults (running a business, writing professional software, dealing with contracts and even coping with tragedy). By the end of the chapter, Bill has matured significantly. At only 16, he has experienced the highs of entrepreneurial success and the lows of personal loss. This period forged many of his traits: a fierce work ethic, leadership skills, and an understanding that life can be unpredictably short (which surely fueled his urgency in later endeavors). The chapter sets Bill up for his final year of high school, where even bigger changes await.

Chapter 8: The Real World

By the time we reach Chapter 8, Bill Gates is in his late teens, and the title “The Real World” signals his increasing engagement with life beyond the insulated realm of school. This chapter focuses on Bill’s senior year of high school (1972–1973) and the broadening of his experiences in both professional and personal spheres. If earlier chapters showed he could handle things beyond his years, this one shows him actively stepping into adult environments.

One major storyline is that Bill, having conquered a lot of challenges at Lakeside, sought new horizons outside school. After Kent’s death, Bill became even more driven to make the most of opportunities. He started thinking about his future – college and career – and also about the wider world of politics and society that had always intrigued him (Kent had sparked Bill’s interest in economics and history, for example). So, in the summer before his senior year, Bill did something quite unexpected for a self-proclaimed computer geek: he went to Washington, D.C. to serve as a Congressional page in the U.S. House of Representatives. This was essentially a summer job where he ran errands and delivered documents for Congressmen. For a 16-year-old from Seattle, it was an eye-opening plunge into national politics. Bill found the Capitol’s goings-on fascinating – he got to witness legislative debates, the maneuverings of elected officials, and the buzz of government up close. He noted that politics had a kind of drama and intensity not unlike what he loved in competitive programming; except here, the stakes were policy and power. This experience grounded him a bit in “the real world” of government and broadened his perspective beyond bits and bytes.

Returning to Seattle for senior year, Bill decided to continue pushing his comfort zone. In a bid to redefine himself (maybe not just be “the computer guy”), he took a daring step: he auditioned for the Lakeside school play. Lakeside was putting on a one-act play, and to everyone’s surprise, Bill won the lead role. Suddenly, he was spending afternoons at drama rehearsals instead of the computer room. This might seem out of character, but Bill actually embraced it wholeheartedly. Memorizing lines and portraying a character in front of an audience gave him a thrill similar to what he got from solving a hard programming problem – it required focus, creativity, and a bit of courage. It also had social perks: during rehearsals, he mingled with a different circle of classmates (including girls, since by this time Lakeside had become co-ed). In fact, Bill had his first real brush with teenage romance thanks to the play – he got to flirt, in character, with his female co-star, a popular girl named Vicki. For a shy nerd, this was a big deal. He later joked about how performing on stage turned out to be a great way to meet girls, even if he was still pretty awkward at it.

This chapter also highlights Bill’s college application process, which he approached with his typical strategic mindset. He decided not to apply to MIT, interestingly, because he thought spending college surrounded by people exactly like him (all math/computer nerds) might be limiting. Instead, he applied to a variety of elite schools and cleverly tailored each application to a different persona: for Princeton he emphasized his technical achievements, for Yale he wrote about his newfound passion for drama, and for Harvard he highlighted his interest in politics and law. This multifaceted approach was successful – he was accepted to several top schools and ultimately chose Harvard University for his next chapter.