Chapter 1: Strategic Concepts and Decision-Making Contributions During Alibaba Period

From 2006 to 2017, Professor Zeng Ming served as Alibaba Group's Chief Strategy Officer ("Chief of Staff"), deeply involved in the formulation and execution of Alibaba's overall strategy. As Jack Ma's strategic advisor, he helped create and develop important business segments including Taobao, Alipay, Alibaba Cloud, and Cainiao Network. During his time at Alibaba, Zeng Ming promoted a series of forward-looking strategic concepts, the most prominent being the platform ecosystem strategy and decentralized organizational transformation.

1. Platform Ecosystem Strategy: Zeng Ming believed that Alibaba's core competitiveness was not in a single business, but in building future commercial infrastructure—various types of platforms or ecosystems. He pointed out that the traditional emphasis on "core capabilities" had become outdated, and future enterprises should develop organically like networks, becoming more biological rather than mechanical. Under his advocacy, Alibaba gradually expanded from an early e-commerce platform to a complex ecosystem encompassing e-commerce, payments, logistics, cloud computing, and more, positioning itself as a builder of social business ecosystems. The Alibaba Group underwent a major structural adjustment from late 2012 to 2013: breaking down the e-commerce business into 25 small business units (BUs), reorganizing financial businesses into multiple divisions, and Jack Ma stepping down as CEO. This transformation was based on Zeng Ming's judgment—"if Alibaba wants to promote the development of an ecosystem externally, the company must also achieve ecologicalization internally". Therefore, Alibaba internally broke the traditional bureaucracy, distributing power and business into smaller, more flexible units, forming an internal ecosystem to adapt to the needs of the platform ecosystem strategy.

2. Decentralized Organizational Transformation: Zeng Ming advocated for distributed collaboration and small team operations as an organizational model to adapt to the rapidly changing environment of the internet era. He participated in formulating Alibaba's "four transformations" policy: marketization, platformization, ecologicalization (species diversity), and data-driven approach. For example, on the Taobao platform, external merchants and service providers were introduced to jointly create diversified goods and services, enabling "small but beautiful" and category-diverse sellers to flourish, achieving more personalized matching between buyers and sellers. At the organizational level, Alibaba abandoned the traditional unified management center and encouraged internal innovation through frontline empowerment and horse-racing mechanisms. As Jack Ma said: "Traditional management is no longer suitable for Alibaba; we need to build an ecosystem that integrates internal and external resources." After the 2013 reorganization, each business unit had greater autonomy, forming a competitive and cooperative ecosystem among them. This decentralized organization laid the foundation for Alibaba to maintain agility in the rapidly changing internet competition. When summarizing Alibaba's experience, Zeng Ming stated that future organizations are more like networks, needing to break bureaucracy and move toward network-based organizational forms. Alibaba provided momentum for the continuous evolution of the platform ecosystem through internal entrepreneurship, partnership systems, and other methods that made the organization flatter and self-driven.

Chapter 2: Zeng Ming's Core Theoretical Concepts

Based on practical experience, Zeng Ming developed a series of strategic management theories, including "Momentum Theory," "C2B Strategy," "New Business Civilization," "De-KPI," "De-Management Center," "Self-Evolving Organization," and "Structural Empowerment." These concepts form the core of Zeng Ming's strategic thinking system. The background, core views, and application cases of each are explained below.

2.1 Momentum Theory

Background: The rise of the internet and mobile internet has created a business environment full of high uncertainty and disruptiveness. Facing these changes, entrepreneurs need to grasp the major trends of the times to succeed. Through long-term research and practical experience, Zeng Ming realized the importance of "momentum" in strategy.

Core Views: "Momentum Theory" emphasizes following and utilizing the momentum contained in era trends to formulate strategy. Zeng Ming advocates that entrepreneurs should have a "ten-year vision," maintaining keen insight into future trends while "working for one year" tactically to find breakthrough points. "The times make heroes," and respecting and grasping major trends is a prerequisite for success. He further points out that leaders should not only follow trends but also dare to create trends. Only by skillfully utilizing momentum (the energy accumulated by trends) can enterprises become leaders of their time. The first principle of strategy is to develop with major trends in a highly uncertain environment to gain momentum. In a word, "without utilizing momentum, it's impossible to become a leader of the era."

Application Cases: Apple, after Steve Jobs' return, captured the major trends of digital music and smartphones, redefining the industry landscape through iPod and iPhone, thus achieving a takeoff. In contrast, PC giant Dell failed to see the major trend of mobile internet, missed momentum, and declined. Alibaba's own development was a result of following the macro trends such as the rise of China's consumer internet and the popularization of mobile payments. Zeng Ming often cites these examples to remind entrepreneurs: during key transformation periods, it's essential to assess major trends with a long-term perspective, and going with the flow can achieve twice the result with half the effort.

2.2 C2B Strategy

Background: In the traditional industrial era, business was dominated by the B2C model (Business to Consumer, where enterprises mass-produce and then sell to consumers). However, with the development of internet and data technology, consumer roles have strengthened, and the market has begun to shift from "seller-driven" to "buyer-driven." In 2012, when discussing with Jack Ma, Zeng Ming proactively proposed the "C2B" strategic concept, believing it to be the most important business paradigm in the digital age.

Core Views: "C2B Strategy," or Customer to Business, emphasizes that consumer demand drives enterprise production and value chain operations, which is a disruption of the traditional B2C model. Zeng Ming points out that C2B means that enterprises must design business processes around customers' personalized needs, achieving customized services on a large scale. He calls C2B the "most basic model of the new business era," and only when C2B emerges on a large scale across industries can the entire business chain be completely restructured by the internet and data. The essence of C2B is a fundamental change in business logic: from the enterprise-led supply chain of the past to a network-collaborative demand response chain. In the traditional model, enterprises first mass-produce standardized products, then stimulate demand through advertising and distribute products through channels; while in the C2B model, enterprises first interact with consumers to explore potential demands through data, then quickly organize resources to meet these demands, achieving on-demand production and services.

Application Cases: The development of the Taobao platform embodies the C2B concept: a large number of sellers adjust their product supply based on consumer search, browsing, and other data, achieving consumer data-driven supply. The Taobao customization, Juhuasuan, and other businesses promoted by Alibaba around 2010 were all explorations of C2B. For example, in the clothing industry, some merchants obtain fashion trends and consumer preferences through Taobao and Tmall, then conduct small-batch flexible production, truly achieving "production based on sales." Zeng Ming predicted that 2018-2023 would be a key period for the breakthrough of the C2B model, with large-scale personalized customization appearing in more industries. He even further proposed derivative models such as "S2B," exploring innovative paths where platforms (Supply/Support) empower numerous small business merchants to better serve the customer end. In summary, the C2B strategy reflects Zeng Ming's judgment on future business models: customer-driven will replace manufacturer-driven, and data will link customized needs with social supply chains.

2.3 New Business Civilization

Background: "New Business Civilization" is a macro concept proposed by Zeng Ming for business transformation in the information age. As the internet deeply penetrates the economy and society, new technologies and values are reshaping business rules, which he calls the emerging "new business civilization." As early as 2009, Zeng Ming gave a speech titled "The Dawn of New Business Civilization," believing that the mass production line and standardization model of the industrial age would give way to new networked and intelligent models.

Core Views: Zeng Ming believes that the DNA of new business civilization consists of two double helices: network collaboration and data intelligence. These two organically integrate to give birth to entirely new business species in the digital era. Network collaboration refers to breaking down complex business activities and having them collaboratively completed by numerous participants through internet platforms, making the process more efficient. Data intelligence refers to the use of big data and AI to continuously iterate and optimize decisions, more accurately perceiving and meeting user needs. Under the new business civilization, business operations are more biological—enterprises coevolve with ecosystems, far more flexible than mechanical hierarchical organizations. He emphasizes that "precision" is the essential difference between new business and old business. The industrial age succeeded through scale, while the new business era pursues precise fulfillment of individual needs: first exploring potential needs through interaction, matching supply in real-time, and providing customized services based on scenarios. Zeng Ming calls this upgrade the transition of business from "extensive scale" to "refinement and accuracy."

Application Cases: Google's search advertising analyzes user intent to achieve precise ad delivery by scenario and real-time bidding fees, which is the embodiment of "refinement" in the new business civilization; Taobao's advertising system can track the entire chain from advertising investment to sales conversion, making every penny's effect transparent, which is the embodiment of "accuracy." Additionally, ride-sharing platforms like Uber use data intelligence to achieve real-time matching and dynamic pricing, but Zeng Ming analyzes that their dilemma lies in the lack of true network collaboration effects—scale effects alone are insufficient to form monopoly barriers. In contrast, Taobao, because it built payment, credit evaluation, and other network collaboration systems early on, although developing slowly, laid the foundation for ecosystem network effects, and once the network matured, it achieved explosive growth. These examples illustrate that the new business civilization places more emphasis on collaboration effects and data-driven competitiveness, rather than traditional resources and scale. Zeng Ming summarizes: "Network collaboration + Data intelligence = Intelligent business", a simple formula that encapsulates the secret to Alibaba's success and reveals all the keys to future business.

2.4 "De-KPI" Concept

Background: In traditional management, KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) are widely used for assessment and motivation. However, in rapidly changing and innovation-driven environments, overly rigid KPI assessments can lead to short-sighted organizational behavior and constrain innovation. While promoting empowerment-type organizations, Zeng Ming proposed the concept of "De-KPI" (breaking free from KPI constraints), believing this to be a hurdle that organizational transformation must overcome.

Core Views: "De-KPI" does not mean completely abandoning indicators, but rather breaking free from the inertial constraints of traditional KPI management and establishing a real-time, dynamic, multi-dimensional indicator system. Zeng Ming points out that if a company promotes empowerment and innovation while still using old-style KPIs to assess and reward employees, employees will ultimately be led by these short-term indicators, making it difficult for the organization to truly transform. Overly simple KPIs distort strategy: many enterprises simplify strategies into one or two numerical targets (such as annual revenue, profit) during execution, which cannot reflect the true requirements of the strategy and instead cause management to sacrifice long-term development to achieve indicators. He stated directly: "Breaking free from KPI inertia is a very difficult but necessary hurdle for organizational innovation." Therefore, new-type organizations need to shift from single KPI orientation to online dynamic indicator matrices. Through digital tools, managers can monitor business health and progress in real-time, evaluating team contributions with multi-dimensional indicators, rather than a few static numbers at the end of the year.

Application Cases: At Alibaba, in the early days to encourage Taobao's rapid market expansion, Jack Ma boldly set the "double million KPI" (enabling 100,000 sellers to achieve annual incomes over 10,000 yuan and bringing 100 million consumers to online shopping within a year), a visionary indicator that at once shifted the team's focus from just staring at GMV (Gross Merchandise Volume). But as business complexity increased, Alibaba gradually de-emphasized hard KPI indicators for various sub-businesses, instead adopting more horse-racing mechanisms, process indicators, and user feedback for evaluation. Zeng Ming also advocated using data dashboards to provide real-time feedback on business status, allowing teams to self-correct without superior orders. This change effectively avoided behavior just for the sake of KPIs, making the organization more focused on creating user value and long-term strategic goals.

2.5 "De-Management Center" and Self-Evolving Organization

Background: "De-Management Center" is an innovative idea proposed by Zeng Ming for organizational structure. Traditional enterprises rely on top-down hierarchical decision-making and centralized management, but in an era of high uncertainty, this model responds slowly and suppresses frontline creativity. To this end, Zeng Ming advocates weakening central control and shifting toward an empowering, self-evolving organizational model that allows the organization to evolve in a self-driven manner.

Core Views: "De-Management Center" requires reducing dependence on a single authority and allowing decisions and innovations to emerge from within the organization. Zeng Ming points out that many leading enterprises today are exploring "operation without CEO commands"—even without boss-level instructions, the organization can operate efficiently in coordination. To achieve this, enterprises need new mechanisms to answer three questions: Without central control, how does the organization ensure healthy operation? How does it maintain the right direction? How does everyone truly collaborate? His answer is: use culture and vision to build consensus, use data and platforms to provide transparent feedback, and use distributed power to stimulate initiative. The focus of management will shift from "control" to "motivation" and "empowerment." As he says, the core of the industrial age was bureaucratic management, while the network age must break bureaucracy and move toward network-type organizations. In such organizations, central managers no longer direct everything in detail, but rather enable frontline employees to make decisions and collaborate through mechanism design. This self-organization can continuously self-evolve, constantly producing high-quality strategic decisions and innovations. "Self-evolving organization" refers to such an organization that dynamically adjusts strategy and continuously emerges innovations under external environment feedback. Zeng Ming emphasizes that in the midst of dramatic changes, being right once is far from enough; organizations must cultivate the ability to innovate continuously—letting strategy and innovation grow "bottom-up" within the organization.

Application Cases: The co-creation mechanism widely implemented within Alibaba embodies the de-management center thinking. Core employees participate in strategic discussions together, dynamically adjusting direction according to market changes, making strategic decisions emerge collectively within the organization. For example, the strategy for the annual "Double 11" shopping festival is not decided by executives behind closed doors, but is optimized in real-time by various business teams under data guidance, eventually forming a global consensus. In terms of organizational culture, Alibaba's "horse-racing mechanism" allows multiple teams to explore similar projects in parallel, with the successful ones prevailing, which is actually a decentralized adaptive evolution. In the early days of Taobao, multiple teams simultaneously developed different versions of product features, "growing wildly" with survival of the fittest, ultimately leaving the solution that best matched users. Similarly, Huawei's "rotating CEO" system and Haier's self-operating entity model are also attempts to weaken the single center and stimulate organizational self-evolution. Zeng Ming's ideas provide a theoretical foundation for such practices: future excellent enterprises should be self-evolving organisms, not machines driven by upper-level centralization.

2.6 Structural Empowerment

Background: "Empowerment" has become a buzzword in management, but Zeng Ming places more emphasis on "structural empowerment", which means embedding empowerment into the organizational structure itself through institutional and tool-level design. This way, empowerment is no longer just a matter of leader attitude but becomes part of the enterprise's operating mechanism.

Core Views: Structural empowerment requires enterprises to build platform systems that enable employees and partners to access needed resources and capabilities at any time. Zeng Ming points out that the future is an era of creativity, where much traditional management knowledge will be replaced by AI, and the greatest value of humans lies in innovation. Therefore, organizations need to stimulate human creative potential through empowerment. Empowerment is not just a slogan but must be implemented at the tool level. He exemplifies that for complex organizations like Alibaba, empowerment must rely on technological tools, among which *"data middle platform"* is a very important empowerment tool. The data middle platform precipitates the data and technical capabilities of various company businesses into universal modules, ready for use by front-end teams, greatly improving the efficiency of innovation and trial-and-error. Zeng Ming explains that the core value of the middle platform lies in allowing front-end innovation to change rapidly, equivalent to providing strong support for innovation. This is a form of structural empowerment: through platformized infrastructure (data, technology, operational support, etc.), capabilities are tooled and distributed to teams, allowing small teams to do what big companies can do. Structural empowerment also includes mechanism-level empowerment, such as equity incentives and benefit-sharing mechanisms, giving employees a sense of ownership, transforming from "I have to do it" to "I want to do it." In Zeng Ming's view, organizational principles are evolving from the past incentive to empowerment and co-creation. Empowering organizations enable talents to create value in a self-driven manner by providing space, resources, and help, rather than relying on manager supervision.

Application Cases: Alibaba is particularly outstanding in empowering ecosystem partners. For example, basic services provided to merchants such as Alipay payment, Cainiao logistics, and Alibaba Cloud computing are a form of "structural empowerment," helping small merchants reduce technical and operational barriers to entrepreneurship on the platform. Another example is Alibaba Cloud's development of open SaaS interfaces, allowing numerous third-party software service providers to connect, which is equivalent to empowering the entire ecosystem to serve merchants together. Looking at the company internally, Alibaba's middle platform strategy precipitates the technical capabilities that were repeatedly built by various business lines, turning them into shared services empowering all business departments, greatly enhancing overall collaborative efficiency and stimulating product innovation in frontline teams. Zeng Ming emphasizes, whoever evolves into an empowering enterprise first is more likely to become a winner in the intelligent business era. This is because structural empowerment enables the creative power of the entire ecosystem to be exponentially amplified, forming a virtuous cycle. This concept is influencing more and more enterprises to think about how to build platforms to empower employees and customers, thereby achieving growth together.

Chapter 3: Key Ideas in Representative Speeches, Articles, and Works

Zeng Ming has systematically expounded the above strategic ideas in public speeches, published works, and articles. This chapter selects three representative works—"Smart Business," "The Dictator's Innovation," and "Fierce for Ten Thousand Years"—to extract his core concepts.

3.1 "Smart Business"

Work Background: "Smart Business: What Alibaba's Success Reveals About the Future of Strategy" is a book published by Zeng Ming in 2018, systematically summarizing his observations and practices during more than ten years at Alibaba. The English version of this book was published by Harvard Business School Press. The book combines numerous Alibaba cases and classic business cases, aiming to provide strategic guidance for the digital age to enterprises in all industries.

Key Ideas: "Smart Business" proposes a refined formula: "Network Collaboration + Data Intelligence = Smart Business". Zeng Ming emphasizes that this equation reveals the reason behind Alibaba's success and is also the essence of future business. The book explains in detail how network collaboration reorganizes business processes that were previously vertically integrated through internet platforms into dispersed, flexible, scalable, globally optimized processes; and how data intelligence records and iteratively optimizes all business data, more accurately mining user needs and providing personalized products and services. The smart business era is therefore defined as: solving problems through large-scale multi-role real-time interaction (collaboration) and continuously optimizing decisions through full-chain data feedback (intelligence). Zeng Ming believes this new strategy is applicable to enterprises in any industry, not just internet companies.

A famous case in the book is Alibaba's annual "Double 11" shopping festival. Zeng Ming calls it a perfect example of network collaboration: Taobao/Tmall itself does not produce a single product, but through the platform, it mobilizes tens of millions of sellers and millions of partners to work collaboratively, fulfilling massive orders throughout the day. Such complex trading activities could not be completed by traditional vertical enterprises, but in the platform ecosystem, various links collaborate to achieve results far exceeding the efficiency of a single enterprise. This proves the power of network collaboration. On the other hand, data intelligence also plays a key role in Double 11: real-time data analysis guides inventory allocation, logistics routing, and marketing strategies, forming global optimization. All these validate the new strategic framework advocated in "Smart Business."

Impact and Evaluation: "Smart Business" comprehensively organized Alibaba's commercial evolution process and strategic new blueprint for the first time. The strategic framework and organizational principles proposed in the book (such as the new positioning theory of point-line-plane-body, the organizational evolution from management to empowerment, etc.) provide thought guidance for numerous entrepreneurs. It can be said that the book integrates Zeng Ming's various concepts proposed over the years (C2B, new business civilization, collaborative effects, etc.) into a systematic whole. As stated in the book: "This is a strategic guide for the digital economy era." Many enterprise executives use this book as essential reading for learning internet thinking and intelligent strategy. Through this work, Zeng Ming established his influence in the field of strategic management academia and industry, being hailed as the authoritative summary of the "Alibaba experience" by "Jack Ma's military advisor."

3.2 "The Dictator's Innovation"

Work Background: "The Dictator's Innovation" is a thought-provoking proposition put forward by Zeng Ming in a certain speech or article. The title carries a hint of humor and contradiction: on one hand, "dictator" refers to centralized leadership with strong power, on the other hand, "innovation" requires diversity and vitality. Behind this phrase actually lies Zeng Ming's unique insights into the relationship between leadership and innovation.

Key Ideas: Zeng Ming points out that in the early stages of innovation and at critical decision-making moments, centralized leadership can often play a key role. He describes how some outstanding entrepreneurs exhibit firmness and decisiveness like "dictators" when driving innovation. This is not derogatory, but emphasizes the importance of clear vision and strong execution for innovation breakthroughs. For example, Zhang Xiaolong, the father of WeChat, adopted an almost decisive style when leading the WeChat product, insisting on a "one-man show" to maintain the purity of the product experience, which was one of the reasons for WeChat's rapid rise. Similarly, Steve Jobs was seen as a "innovation dictator" in Silicon Valley, and his personal pursuit of perfection and decisive decision-making created Apple's disruptive products. Through these cases, Zeng Ming points out: in rapidly changing innovation fields, a visionary leader needs to centralize decision-making power at critical moments, boldly try and error, and even break bureaucratic resistance with personal authority. This "dictatorial" leadership can escort innovation in its early stages.

However, he also emphasizes that "the dictator's innovation" does not mean one person accomplishes everything. On the contrary, successful "innovation dictatorship" is often built on stimulating team passion and keenly capturing user voices. Once the innovation direction is verified as effective, leaders should timely delegate power, allowing broader creativity to participate. Zeng Ming's view reflects a consideration of dynamic balance in leadership: innovation needs a relaxed and free atmosphere, but also needs strong leadership to anchor direction in the initial chaos. As he said, "the most important core ability of enterprises today is not whether a strategic decision is right or wrong, but whether there is a system that can continuously make strategic judgments and corrections." If the initial autocracy can evolve into later openness and co-creation, then the enterprise will have both explosive power and sustainability.

Application Examples: Many of Alibaba's early product innovations also embody this point: for example, when Taobao was first created, Jack Ma insisted against opposition on not charging commissions from sellers (free model), a decision with a strong personal style that created the miracle of Taobao rapidly accumulating popularity. Similarly, when Alipay was initially promoting guaranteed transactions, it faced questioning, and Jack Ma ordered "do it first, talk later," and this determination is also a manifestation of "dictatorial" innovation. It was later proven that these decisions opened new chapters for Alibaba. Through "The Dictator's Innovation," Zeng Ming reminds entrepreneurs: in an era when thousands of troops are exploring innovation, don't just pursue democratic consensus and fall into mediocrity; sometimes you need the courage to break through forbidden zones alone. Of course, he also calls for turning successful experiences into the collective wisdom of the organization after "dictatorship," using mechanisms to make innovations continuously emerge, rather than forever relying on individual heroes.

3.3 "Fierce for Ten Thousand Years"

Work Background: "Fierce for Ten Thousand Years" is a rather jianghu-flavored expression, originating from a themed speech or article title by Zeng Ming (the specific source is often entrepreneurial forums or Hupan University sharing). This phrase sounds exaggerated but reflects his unique interpretation of entrepreneurial spirit and has become a motto circulated among entrepreneurs.

Key Ideas: "Fierce" means strong, brave, not afraid of challenges. "Ten Thousand Years" symbolizes an extremely long time span. Connecting the two, Zeng Ming uses this humorous phrase to emphasize that entrepreneurs must have lasting determination and fearless spirit. The core ideas include: courage and tenacity. First, the entrepreneurial journey is full of unknowns and difficulties, and only a "fierce" mindset can break through barriers—this means daring to break conventions, boldly trying and erring, not fearing failure or mockery. Second, "ten thousand years" implies long-termism. Zeng Ming repeatedly advises entrepreneurs that great undertakings cannot be accomplished overnight, and they must be prepared psychologically to persist day after day for ten years. Just as Alibaba proposed to be a "102-year company," this is a symbol reminding enterprises to take a long-term perspective and continue to strive for the future. Therefore, "Fierce for Ten Thousand Years" can be understood as: persisting to the end with aggressiveness and perseverance. No matter how external circumstances change, truly excellent entrepreneurs must have both the vigor of newborn calves not fearing tigers and the persistence of water dripping through stone.

Application Examples: Jack Ma and Alibaba's growth process is exactly a portrayal of "Fierce for Ten Thousand Years": from the 18 founders starting the business in 1999, to adhering to beliefs when the internet bubble burst, to later e-commerce wars and financial storms, in the face of every severe challenge, the Alibaba team displayed extraordinary resilience and courage, ultimately surviving harsh winters and winning victories. This spirit has also influenced the students of Hupan University. Zeng Ming shares many failure cases in Hupan classrooms, aiming to prepare entrepreneurs psychologically for "nine deaths and one life," facing the winding road of entrepreneurship with strong will. He says: "The greatest enemy of excellence is being content with goodness," and only by maintaining a fierce upward momentum can one continuously climb to new heights. Therefore, this phrase is both an encouragement to entrepreneurs and an extension of Zeng Ming's strategic thinking at the human level: strategy is not only analysis and planning but also needs the support of spiritual strength. It is this style of both rational insight and passion that makes Zeng Ming's speeches widely welcomed by audiences and also injects confidence and fighting spirit into countless entrepreneurs.

Chapter 4: Systematic Summary and Outlook of Enterprise Strategy, Organizational Management, and Innovation Methods

Integrating the above ideas, Professor Zeng Ming has constructed a strategic management system for the intelligent business era, systematically summarizing enterprise strategy formulation, organizational management, and innovation methods, and making forward-looking prospects for future development.

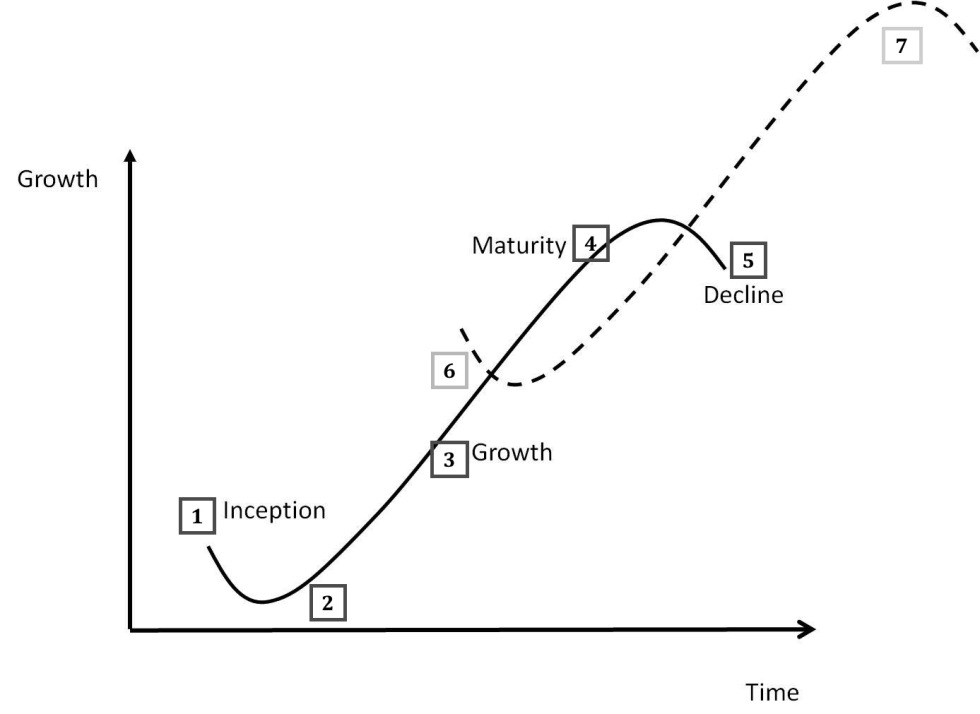

1. New Paradigm of Strategy Formulation: Traditional strategy seeks to reduce uncertainty, formulate long-term plans, and execute efficiently. But Zeng Ming has redefined strategy: strategy is no longer a static plan, but a dynamic process of repeated iteration between Vision and Action. He proposed the "AV cycle" (vision-action rapid feedback loop) model. Specifically, enterprise leaders must first have a long-term industrial endgame judgment (Vision), but under rapidly changing environments, any prediction may deviate, so what's more important is the continuous process of "prediction-experimentation-correction". Action itself becomes an exploration tool: rapid execution, small-step trial-and-error, validating or correcting the initial vision from market feedback. This cycle repeats itself, allowing strategy to self-adjust and develop. Zeng Ming emphasizes: "What's important is not whether the prediction is right or wrong, but whether you are constantly making predictions." Through high-frequency iteration, enterprises can find certainty in uncertainty. He also points out that wasting some resources is worthwhile to quickly test and find direction; internet companies dare to progress on multiple lines and conduct redundant experiments for this reason. This shift in strategic thinking has enlightened many traditional enterprise managers: rather than trying to formulate perfect plans, it's better to learn while doing, seeking the optimal path in dynamics.

2. New Principles of Organizational Management: Zeng Ming's summary is that future organizations must transition from "management-oriented" to "empowerment-oriented". Management-oriented organizations rely on hierarchical commands and KPI assessments, suitable for stable environments; while empowerment-oriented organizations emphasize network collaboration and creativity, adapting to the rapidly changing intelligent era. Specific new principles include: vision-driven replacing instruction-driven—letting all employees understand the company's long-term mission, uniting through shared vision rather than constraining through regulations; culture and mechanisms replacing hierarchical control—guiding behavior through values, equity incentives, shared results, rather than through administrative orders; empowerment replacing management—leaders' roles changing from commanders to coaches and servers, providing resource platforms for the frontline to create greater value; co-creation replacing top-level decision-making—encouraging employees to participate in strategic discussions and innovation projects, forming bottom-up decision emergence mechanisms. Additionally, organizational structures will become more flattened and elastic. Zeng Ming deduces that the best form for creating new businesses in the future may be "special forces"-style small teams: a dozen people working closely together can support an entrepreneurial project. These small teams, supported by the company's internal loosely coupled platforms, plus externally open network collaboration, form a three-layer organizational structure of "tightly coupled small teams + loosely coupled platforms + open networks". In this form, efficient execution will increasingly be undertaken by AI, and human energy will focus on creating unique value. In a nutshell, future organizations are a kind of human-machine collaborative, network-evolving organism: AI handles tedious affairs, humans exert creativity, and the two collaborate in operations. This series of new organizational principles by Zeng Ming provides operational guidelines for enterprises transitioning from industrial paradigms to digital paradigms.

3. New Approaches to Innovation Methods: In the field of innovation, Zeng Ming particularly emphasizes embracing uncertainty and cross-border integration. He points out that uncertainty means opportunity, and true strategy should grasp potential demands that have not yet manifested. Therefore, enterprises should encourage exploratory innovation, preferring to experiment in multiple directions rather than adhering to a single direction. Alibaba's internal "horse-racing" mechanism is precisely to maintain diversity in response to an uncertain future. Zeng Ming also mentions the "point-line-plane-body" strategic thinking to guide different innovation paths: point breakthrough (single-point innovation like Uber focusing on ride-hailing), line integration (building an industry chain), plane orientation (creating multi-sided market platforms), and finally body as an ecosystem. Different enterprises should choose suitable innovation paths based on their own situations. Additionally, he is very concerned about technology-driven innovation. In recent speeches, he has discussed how AI technology is triggering business paradigm changes: "AI essentially solves the problem of decision efficiency and costs, with its core value lying in creating new supply." As artificial intelligence develops, machines will liberate people from repetitive, boring mental labor, giving people more time to engage in creative matters. This will give rise to many previously unimaginable new products and services. Zeng Ming predicts, "In principle, there will be no 'product companies' in the future, only 'service companies,' with products merely being carriers of services." In other words, enterprises need to transform into user-centered, scenario-based service providers. To meet this trend, he suggests that enterprises accelerate digital and intelligent transformation, using AI, big data, and other technologies to upgrade business models. In terms of organizational and intelligent entity co-creation, he depicts a future picture: AI becomes employees' "colleagues," organizational structures are redefined, and human-machine integration produces new work paradigms. Facing such a future, he encourages enterprises to maintain a spirit of lifelong learning and self-revolution, proactively embracing technological changes, even if it means overthrowing their old models. This self-iteration is the embodiment of the "self-evolution" spirit advocated by Zeng Ming at the innovation level.

4. Future Prospects: Zeng Ming is full of confidence about business transformation in the next 10 years and beyond. In his view, human business society has experienced agricultural economy and industrial economy, and is now entering a new era based on intelligent technology. This is a civilization-level leap. In his second "Looking Ten Years Ahead" public lecture, he pointed out that the AI era has arrived, like welcoming a new "iPhone moment." He predicts that three major technological mainlines—General Artificial Intelligence, Autonomous Driving, and Scientific Intelligence (AI for Science)—will reshape various industries. The underlying logic of enterprise value creation will also change—in the past, information asymmetry was a business opportunity, now AI makes information matching tend toward perfection; in the past, insufficient production capacity was the norm, now production overcapacity requires mining potential demands. Therefore, he believes that "uncertainty is the opportunity for creation". The essence of strategy will become more synonymous with innovation, with every executive and even every employee needing to possess strategic thinking, closely integrated with product technology. Zeng Ming also has prospects for talent: the future most needs creative talent with multi-dimensional perspectives and unique specialties, because AI will lower the threshold of professional knowledge, and composite creative talent will stand out. He encourages the younger generation to engage in learning cutting-edge technologies such as AI while cultivating humanistic insights, in order to lead innovation in the era of human-machine collaboration.

In summary, Professor Zeng Ming's strategic thinking system has painted for us a new blueprint for the intelligent business era: enterprise strategy must have the foresight to follow trends, as well as the agility for rapid trial and error; organizational management must be people-oriented and network-collaborative, allowing organizations to self-evolve like living organisms; innovation methods must dare to break boundaries, make good use of new technologies, and transform uncertainty into growth momentum. Looking toward the future, this system of thinking will continue to guide enterprises in finding the right direction amid turbulent technological changes and achieving sustained prosperity. As Zeng Ming says: "It takes ten years to achieve greatness," only by seeing the major trends, adhering to the mission, and continuously innovating can one stand invincible in the wave of new business civilization.